This weekend, I remember Ijo Dee

As the notable Nigerian band of young dance artists, IJO DEE flags off the second edition of its yearly festival of African dances this weekend, I recall a grand exploit that launched the troupe of youngsters on the world stage. (Stories were first published in 2003)

IJODEE, NIGERIAN TROUPE, WOWS THEM AT INTERNATIONAL DANCE MEETS

Mihari, the pretty hostess attached to the Nigerian troupe at the on-going Sanga 3, the international festival of choreography and dance, holding in Madagascar, waved excitedly at Dayo and said "no kain". She followed it up with a generous smile, which no doubt suggested she was happy with herself

She has caught the bug just like all the rest of her fellow Malagasy and participants at the festival who have since adopted the seven-man Nigerian troupe as some kind of folk heroes.

Here in Antananarivo, the Madagascar capital where the festival --the fifth edition of the African and Indian Ocean Choreography Platform -- is holding , almost every other person wants to learn and speak the Nigerian pidgin English. "They love our pidgin so much and they want us to teach them; they compare it to the patua of the Jamaicans… but they are even more surprised when we told them that it was the inventions of the Nigerians", stated Victor Eze, the administrator (manager of the Nigerian team)

And almost every other person, particularly among the participants, want to be in the midst of the Nigerians. They think that the best place to catch unrestricted fun is right there in the camp of the Nigerians.

Indeed, the Nigerians are the cheer-leader at this dance feast. They are the one to lead at the various interactive sessions -- these are gyration- like informal gatherings held every night at the Soarono Station , a currently disused train station which serves as the dining centre for the almost 2,000 participants from around Africa and the Indian Ocean .

Once the band launched the music, usually the first set of dancers to be on the floor is sure to be the Nigerians. They translate the Malagasy music into the Nigerian local dance icons – Ekombi, Bata, Koroso and so on.

Perhaps, only the Senegalese get to beat the Nigerians to the dance floor . But even the West African neighbours can’t match the upbeat groove of the homeboys. At this festival the crowd just loves the Nigerians; and can’t seem to get enough of them.

"Your people are so free and happy; I love their spirits", stated Stephen Ochalla, artistic director of Kwoto Art Centre, who is representing Sudan at the festival. "There is so much confidence in the Nigerians; and they dance well. I can’t wait to see their show", stated the dark, gangling Sudanese.

"I know that the first prize is for us. I can feel it, even from the feelers that one gets from other participants, it is sure that we have something unique to offer; and everybody thinks highly of our team", boasted Eze, himself an experienced actor and dancer who toured Europe extensively with cast of Wole Soyinka’s King Baabu.

Nigeria’s representatives at the festival is Ijodee Dance Company, a troupe of seven led by Adebayo Muslim Liadi.

Ijodee is not in Madagascar on Nigerian government’s sponsorship but it had been facilitated to the festival by the French Cultural Centre, Lagos. The centre under the leadership of Joel Bertrand had organised a competiton through its no yearly ‘Dance meets Danse’ programme that featured local troupes at is Kingsway Ikoyi Road premises last August.

Ijodee came top. Their prize is the current engagement; to represent Nigeria at the fifth African and Indian Ocean Choreographic Platform which began on Saturday and will end November 15.

The festival dreamt as far back as 1992 had begun in Luanda at which Omitun, the Ibadan-based troupe came fourth. But since the French choreographer, Salia Sanou won the First Prize in 1997, the festival has shifted its base to Anatananarivo, capital city of Madagascar, which then hosted it in 1999 and 2001 with Sanou as Artistic Director. This is the third edition And things are looking up, pretty well, for the Nigerian chaps.

At their workout on Monday morning at the Albert Camus Cultural Centre, right in the centre of the city, Ijodee cast and crew were in great spirit. No one who had seen them during the dinner and the gyration the previous night at the Soarano Station would probably believe they were the same fun makers. They were in the serious business in the work-out with the team’s leader, diminutive Liadi in charge of the muscle – stretching exercises. Saidi Ilelaboye, who doubles as the musician (drummer) and Technical Director, was sweating it out with the Centre’s technicians to set the stage for the team’s technical rehearsals billed for later in the day.

Their first show was yesterday when Liadi did his solo at the Theatre Isotry in another part of the city, where on Monday night, the South African duo of Solo Pesa and Valerie Berger had a three-in-one stupefying show that drew a standing ovation.

Liaidi’s Ido Olofin, a robust ritual of cultural rediscovery, pulled a successful shot yesterday. This was clear from the response of the audience. He hardly could walk out of theatre free as captive troupe of fans and admirers encircled his feet -- those same little muscular feet that had moved as if possessed of the spirit of a grinding machine.

There is already a call for Ido Olofin encore. Tonight, the competition section of the festival begins and Ijodee company is offering Ori (The Head), which Liadi explains as a spirit linked to power of artistic intuition

Adebayo Liadi, a graduate of Senegal International Centre for Dance and Choreography says, "I use traditional dance and music as source of imagination or as a glossary of composition. The choreography leaves its root and returns to them just as it feeds on a variety of influences an styles without ever letting itself be misled. It draws from these languages to create something decidedly unique".

Ijodee Dance Company founded in 1998 is only one of the 11 companies elected from 82 (from 32 countries) that applied to participate in the festival. Aside of Nigeria, there are also Ethiopia; Senegal, South Africa, Niger, Mali, Chad, Egypt, Mozambique; Cape Verde and Burkina Faso.

Back to Eze, the articulate administrator of the Nigerian team, who himself has become a star participant at the festival’s Administrator Workshop based on the quality of his contributors to the discussions.

The festival, he says, is an eye-opener to the many possibilities and potentials of the Nigerian dance artiste and culture industry in general.

"We are yet to perform, yet there is so much respect for us. There is even fear that these Nigerians will do wonders. I wish they know that back at home, the dance artiste and the artiste in general is a nonentity to our government and the public in general".

Sanga 3 is organised by Association Francaise d’Action Artistique (AFAA) and National Office of Arts and Culture Madagascar (OFNAC) with supports from the Madagascar Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European Union Delegation to Madagascar and Intergovernmental Agency of French Speaking Nations

IJODEE, NIGERIAN DANCERS, CAME TOP AT FESTIVAL IN MADAGASCAR

In Madagascar, right in the middle of the Indian Ocean, the name of Nigeria is on the lips of many people. The country’s representatives at the fifth African and Indian Ocean Choreography festival, IjoDee Dance Company came first ahead of 10 other troupes that competed for the grand prize.

The seven-man IjoDee Company had presented its contemporary dance creation entitled Ori (The Head) on Wednesday and the 11-man jury headed by the Ethiopian film maker, Abderhamane Sissako, thought it had the best package as far as the criteria for the competition go.

According to Sissako, the Nigerian won the first prize because they were "original, sincere and sensitive to their culture and the language of modern dance". Besides, he added, "they were very professional in their approach and, inventive."

Trailing Nigeria in the second and third places were Mozambique and Mali. Adedayo Muslim Liadi, leader of the Nigerian troupe and the choreographer whose feat had suddenly made him the toast of the over 2,000 participants from Europe, American, Africa and the Indian Ocean, was overjoyed at the achievement. He kept screaming, "I give thanks to God the almighty for his blessings and gift of life. I thank him for the strength he gave me and my dancers, and the talent and skill he has endowed me with."

Asked how he felt at winning the prize, Liadi said, before the announcement, "I was tensed because I did not know what might happen. But I had seen it already that God was going to do wonders in my life this year. I felt it and now it has happened. I give all the glory to God and to my people back in Nigeria who have always given me support. I thank the French Cultural Centre for their support all the time and to come here.

"I thank the Nigerian artists’ community too because this glory is for all of us. It is tonic for us to do all the best that we can do. The world is there for us all if only we try hard and believe in ourselves and our culture"

Liadi’s Ijodee had come top at a competition organized among about 20 Nigerian dance troupes by the French Cultural through its yearly Dance meets Danse programme held last July at its Aromire (former Kingsway Road) Street, Ikoyi Lagos premises.

On the factors he thought could have given his company the topmost prize ahead of the other contestants, Liadi said; "One is originality; yeah originality; because I refuse to leave my root; I refused to get out of where I come from. And that is a lesson for all of us African artistes. Don’t ever leave your root. Never. Always tap from it and build on it; because its yours."

The diminutive choreographer continued: "if you watch all the other groups that contested, they were very good -- good movement, good form, but the problem was too much of European stuff. But all my movements are from Africa… from swange (Benue), Bata (Yoruba), Koroso (Hausa), Atlogwu (Ibo), Ekombi, (Cross Rivers) and even from Senegal, Benin Republic, Mali…all of them .. I refused to get out of my Africanity. I am going to retain it because it has paid me today and it will surely pay me everyday; I am sure."

Also, Liadi thinks that his feat will now open up a world of opportunity for Nigerian dancers and artistes in general. "I know that thousands of Nigerian dancers will have people from all over the world coming to them.

"There are a lot of scouts here who have seen what we are able to do with our arts and I am sure they will all want to explore Nigeria further."

For the Nigerian culture sector, Liadi feels that this feat which is "like winning the top prize at the dance olympics should make our government to recognise the importance of culture in world politics".

For their feat, Ijo Dee Dance Company formed in 1998, has earned the opportunity to tour Germany, Belgium, France, London, Spain, Tunisia and Italy between February 28 and May 7 next year. And in 2005, it will do an extensive tour of Africa. The tours are the dreams of every professional dance companies.

The biennial festival had begun in 1995 in Luanda but the last three editions since 1999 (and including the current edition) have been held in Antananarivo, the Madagascar capital city

WHEN DANCE RULED THE INDIAN OCEAN WAVE

MADAGASCAR, the beautiful country located on the Indian Ocean, has made name for itself as host of a most important cultural programme for the blacks and African world. Since 1999 when it decided to host the African and Indian Ocean Dance Platforms, the country of 16 million people has, no doubt, wormed itself into the hearts of dancers and choreographers as well as patrons of the art from around the world.

And for tourists with penchant for the physico-emotional performance art, the dance festival is gradually becoming a biennial pilgrimage. They troop in every season to have had a full feasting on the choreographic art as well as on the various crafts of the people of the country.

The government of the country must have been sufficiently informed by certain progressive and divine vision to have convinced the main promoters of the project, the AFAA (Association Francaise d’Action Artistique or French Association for artistic Actions), to move the dance programme to their land.

This year, between November 7 and 15, that the country hosted the festival, it played host to an estimated 2,000 visitors, including the over 300 participants from about 20 countries on the continent of Africa.

There were also guests from the United Kingdom, United States of America, The Netherlands, Germany, Latin and South America as well as from Asia. These included scouts who came to shop for dancers, choreographers and programmes for their various festivals and art centres; tourists; and experts who functioned in the festival as officials, members of the jury among others.

It was the third time Madagascar would be staging the festival hence the acronym, Sanga 3, and its success must have satiated the country's leaders who declared at the closing ceremony that their people had come to see the platform as part of their national heritage.

Madagascar's Culture minister, Odette Rahaingosa, indeed, said plans had already begun in earnest for the next edition in 2005. She noted the development, which the festival had brought to the professional activities of the country's performing artists. Since 1999, she said, many more professional dance groups have emerged on the Malagasy stage and; the fortunes of artistes in general have improved immensely.

And though the minister, on behalf of the country's government, had reason to quarrel with certain aspects of the festival, like the dance presentations of the Mozambiques, Projetos Cuvilas, in the competition category -- in which five adult ladies were paraded nude for about 20 minutes -- she still welcome a continuation of the festival in the country.

The artistic director of the festival, the Burkinabe Salia Sanou, also acknowledged the fact that the platform has indeed found a home in Madagascar. Sanou, himself, the 1997 winner of the festival's grand prize, had started his directorial work on the Sanga with the 1999 edition, which was the first for the country.

In reviewing the 2001 edition, he said: "I think Sanga 2 turned out very well, and when one considers the number of applicants for the event this year (2003), one can only take satisfaction in the success of this competition that created more and more interest from dances and choreographers who want to experiment with other ways of creating, to revitalise the art of choreography and to express themselves."

There was an unprecedented 82 applications for this year's festival competition, out of which only 11 were eventually chosen. This attests to the growing importance of the Platform.

Sanou explains that the selection of the 11 finalists -- out which Nigeria's Ijodee emerged the first prize winner -- was done by a jury composed mostly of the younger generation of dancers, all of whom had taken part in the festival in the past.

These jury members included Opiyo Okasch (who was recently in Nigeria for a workshop as a guest of the French Cultural Centre), Faustin Linyekula, Seydou Boro, Patrick Acogny. There were also Africans from the Diaspora such as Georges Momboye.

Speaking specifically on the strong points of Sanga 3, unassuming Sanou, who throughout the event appeared no more than like any other guest at the event, said: "Well, of course, the competition itself, for which the finalists are working hard to prepare, but also the 'Let's dance' platform, which really is a strong point insofar as it brings this art to a wider audience, and in particular a Malagasy audience.

"This platform also makes it possible to relieve the stress of the competition, because the entrants can perform freely, not under the gaze of the jury, but in front of an appreciative audience. Moreover, a programme has been set up that is a springboard for young choreographers and that covers a fairly complete spectrum of choreographic creativity in Africa and the Indian Ocean.

"Finally, the time devoted to exchanging information and experiences provided by the training schemes are a very important aspect of this platform. All these events form a whole, the various different centres formed by the competition, the programming, opportunities for exchange such as the round tables, all complement one another and make it possible to raise standards every two years.

As a result of the recurrent problems engendered by the competition aspects of the festival, including the obvious and sometimes exuberant, struggle for the prize by the dance companies at the expense of true artistic productivity, there had been call for a cancellation of the competitive programmes in the Sanga. But Sanou, says: "In the beginning it was impossible to do anything other than a competition, because there were not enough African companies to create a strong programme. This time 82 companies have applied. That is no mean thing. Next year, there may be as many as 150. A lot of high quality choreographers have emerged, and gradually the context of a competition will become obsolete and it will be possible to organise an attractive, large scale festival that will give more exposure to African and Indian Ocean modern dance in the long term than could be done by a competition.

Sanou is particularly happy that through the platform, a new work of choreographers is emerging on the African continent.

"This movement has made it possible to raise real questions about working environments and conditions. I think that the infrastructure being built will also enable Rencontres (Sanga) to rise to another level, as with better working conditions, more venues open to dance and more research facilities, we are going to see more and more high quality performances.

Interestingly, rather than the usual prize money always given to winners of art festivals, Sanga has come up with a more productive reward, which at least, will keep the companies working in the future. The prize money that had been awarded to the first three winners has been replaced by an international tour and Sanou, who was instrumental to the new decision, says this would remain a continual policy.

He says: "I have always thought that the jury's decision ought to be rewarded by more than just a sum of money, and that the prize should serve to encourage and help the winning company to develop. That is why an extensive tour must be one of the finest presents one could give the winners.

"A tour certainly enables a company to gain recognition, but beyond that consideration, it shows the company that the work it did is of value. This also helps to structure the winning companies, because the more they tour, the more experience they acquire in artistic and administrative matters.

"A tour bonds the team and helps it to project itself into the future. It forces companies to organise themselves. One must not forget that most applicants come to the competition with no administrative experience. This prize is therefore a real help to the companies in structure and planning.

How IjoDee, Nigerian Troupe got the green in Madagascar

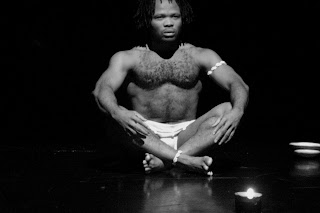

On a day degenerate art seemed to rule the soul of the dancer’s stage, dance steeped in swift, dynamic and melodic riff etched the Nigerian dancers in the heart of the international audience that sat mesmerized in the Alber Camus Theatre on L’Independent Street on Wednesday night.

While the Egyptians mounted a pop art that oscillated between pantomime and agit-prop and the Mozambicans paraded starkly naked maidens in wild, spasmodic and erotic steps and the Chadians did a dance drama with semi-nude characters, the Nigerians did the real dance of the night and got the audience clapping and clamouring for more, long after the 30 minutes duration of the act had lapsed.

The three other shows indeed, confounded critics and discerning members of the audience on the direction of so-called contemporary modern art. And it is not impossible that the open display of naked bums and boobs by the Mozambicans, and the balls by the Chadians must have offended moral sensibility of the elite audience many of whom came with their children.

The Nigerians gave the delight as they engaged their feet and supple bodies in poetic flight into the world of rituals to tell the story or Ori (The Head) or Destiny. Though there were some incoherent movements and gestures here and there and, a problematic technical input nearly ruined the smoothness of the show, the jury and the audience made up of co-participants in the festival and other select mmbers of the public, thumbed up the Nigerian how.

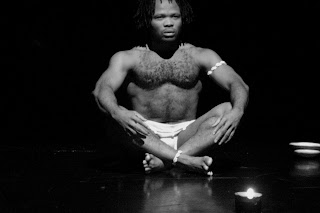

• Dayo Liadi

The presentation by IjoDee was an intensely expressive piece of dance that also gave ample room to drama and pantomime. The music of Ori, contrary to the weird assemblage of sounds that obtained in some of the other works presented throughout the competition, also relied heavily on evocative melody, inventive chants and layers of cross-border musical inflections, to express the mysteries of life and the beat of man’s journey through life in the hands of unknown forces encapsulated in the unseen character called Ori.

Prior to the last Wednesday show and, in fact, since November 8, beginning of the eight-day 5th African and Indian Ocean Choreographers Platforms in Antananarivo, the capital city of Madagascar, IjoDee Dance Company’s members had been held as some sort of celebrities.

They were popular. Immensely beloved.

Everyone seemed to have bought into them.

And the fame had nothing to do with the usual Naija-for-show, the notorious boisterousness of character easily discernible in the style and carriage of an average Nigerian person.

The warmth shown the Nigerians had nothing to do with the fact that the seven-man IjoDee had its own exuberances and, was loud with a bit of nuisance traits in carriage. That was expected of course of a team of very young cast, which with exception of the team leader, the manager and the technical director, were having their very first exposure on an international stage. The love had so much to do with the quality of work expected from the team.

The over 2,000 participants in the festival from about 18 countries had a mindset of reverence for the Nigerians. Much of it had to do with the record of the team-leader, Adedayo Muslim Liadi, who indeed has done quite a good work moving around in the European dance circuit. Having worked in Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels and then pounded the African circuit well, his reputation seemed to have preceded him at this biennial dance meet named Sanga 3 – the third in the Madagascar capital city since 1999.

Even the chief dreamers of the project, unassuming French choreographer Salia Sanou (artistic director of the festival) and Senegalese Germaine Acoigny, appeared to have rested much hope in Liadi to set a fresh agenda for an emergent African choreographic vocabulary, which no doubt, is an underlying agenda of the festival.

In fact, shortly after the show -- at the interactive session usually mounted every night in the disused Soarano train station -- an excited Acoigny sprinted to the table where the IjoDee cast and crew sat swimming in the admiration of their fellow artists, pulled Liadi up and gave him a rounded hug:

‘You have done me proud. I am very happy with you”, she said in her Frenchised English. Then turning to other members of the team, she sang,” You have done very well all of you. We are all very happy with you. Good job all of you.”

And next, in motherly gesture, she cuddled Nneka Celina Umeigbo, the only female member of the team, saying: “but she is the best… you are all very good but the girl is the best. You see what the woman can do? Everything that a man does, the woman does it well, so she is the best”

By now the whole house seemed to have directed its attention to the table. Perhaps it was Acoigny’s deep bass that fills the house even when she speaks softly. Perhaps it was the mood carried over by the crowd from the Albert Camus Theatre… they just couldn’t stop discussing the Nigerians, even after the jamboree of boobs and balls by the Mozambicans and the Chadians, had faded into insignificance.

• Ijo Dee in performance

Soon, the brief motherly affection by Acoigny launched a sort of pilgrimage to the glistening aluminum-cast dining table where the IjoDee cast and crew sat. Especially, the score of journalists from Europe, the United States, Canada and Britain wanted to know what made these chaps from West Africa so thick and confident.

Acoigny, first director of the famous Senegal International Centre for Dance, is revered in the African (and French) dancers’ circuit as a matriarch of the choreographic art. Liadi had been opportune to train under her in Senegal school -- which is however, unfortunately, currently shut down due to paucity of fund. Her attestation to the quality of the Nigerians’ show was an endorsement of some sort.

Stephen Ochalla, the only choreographer from Sudan who flew in from a 10-month Residency programme at a dance institute in Amsterdam in The Netherlands, sat next to Liadi and his excited team; he shook his head and declared: “ These Nigerians have won, I am sure”

But noticing the incredulous look on the face of a reporter, also at the table, he asked: “You don’t believe me? You will see. They are the only one that really danced on stage. The others were doing movements and sports and seemed confused about the meaning of contemporary modern dance. But the Nigerians, they understand modern dance very well and they have not lost their identities like the others”

Since the beginning of the festival, Ochalla, artistic director of Kwoto Dance Institut in Khartoum, had been deeply worried about the direction of the contemporary African dance, as reflected in the various presentations of the about 11 competing companies and 12 other soloists at the festival.

Between himself and the Zambian Georges Daka of Zuba ni Moto Dance Ensemble, (who was also featuring in the non-competitive solo choreography events), they had had countless informal seminars on the emerging submersion of the identity of the African dance in the, according to Daka -- ‘new madness called contemporary modern dance’. They felt uncomfortable as they saw their fellow African dancers and choreographers deliberately committing what could be termed ‘cultural suicide’ just so to speak the dance language of Europe and the West.

The two artistes, mature and (no doubt) idealistic, saw the dawning of a dangerous trend in which, in no time, the African dance artiste would have been stripped of his own cultural philosophy; the very essential that ought to define, at least, the content of his art.

“Our dancers are trying too much to be Europeans, they forget that African art must be rooted in the ideas of the people. This is dangerous”, an exasperated Ochalla sighed.

Daka contextualised the trend in the long-drawn struggle between the West and the rest of the world, already enunciated in the undercurrents of globalisation… “This looks like another scheme to strip Africa of its identity and make us speak like the colonisers. It seems that Europe wants to kill what is ours and then make us take only that which is theirs”

“Really, I don’t see much dancing in what our people are doing at this festival. We have to be worried that all they are doing is just moving and expressing forms without dancing. We have to be very worried about that; about the future of dance in our continent and how our people will relate to most of what our boys are doing now”

Continued Daka, “It is good to learn the skill of creating new forms and techniques from Europe but we must always return to the root of our dance art”.

Ijo Dee on duty.. in Madagascar

Interestingly, Daka seemed to have been speaking to the conviction of Adedayo Muslim Liadi, the Nigerian representative at the festival.

The festival programme note celebrates Liadi’s choreographic virtues as the ability to take off from his cultural root, take a wide flight into the fairy-like space of the West with all its fleeting characteristics and then return to the very earth that nurtured the vision and imagination at the onset.

Stated the note: “The choreography leaves its roots and returns to them, just as it feeds on a variety of influences and languages to create something decidedly unique”.

Liadi indeed, had hinted of his mission as a choreographer on Tuesday at the downtown Isotry Theatre when he gave his non-competitive solo show. He presented Ido Olofin, a ritual enunciation of the travails of modern man who in the lust for acquisition of impurities and imperfections, has lost the ability to interrogate the essence of his existence and nurse the origin of his being.

The choreographer offers in the piece rebirth rite as not an option but a necessity for atonement and spiritual regeneration. After a season of trials, drought and spiritual dislocation, an appropriate propitiation will bring the rains and the greens; he suggests.

But in the solo show that lasted 20 minutes, Liadi traversed and as well criss-crossed the many cultural boundaries of geographical Nigeria. He did this in a lot of colours, movements and graceful steps. These virtues he also brought to bear in the group show, Ori. And these were the virtues that wormed the Nigerians into the heart of the audience on Wednesday

Out of the seven groups that had featured, as at Thursday, in the competitive category, IjoDee stands in a class of its own. It is perhaps only the South Africans that have come close in terms of dynamics of expression in which there is symphony between content, form and techniques. The rest have been laying emphasis on either one or two of the characteristics of a complete choreography.

• The Mali troupe at Sanga 3

• The Mali troupe at Sanga 3

Instructively, while the African dancers, in their obviously unformed and confused voices, struggle to speak western choreographic vocabulary, Valerie Berger, the French choreographer-dancer presented a show that was steeped in African rhythmic culture. She reached deep into the African cultural materials and set same in the context of modern forms and techniques and passed her message easily in Cornered and Lucy, which she presented on Monday. This was not the case with the South African Sello Pesa, her sparing partner who seemed lost in the wilderness of identity; just like many of his comrades from the continent.

Back to the Mozambicans:

The show discomforted the government of the host country, Madagascar that the President insisted that the ‘nude dancers’ must not be allowed to present the dance at the closing ceremony.

The President said his Minister of Culture had told him that the dance was offensive to public morality.

The organisers were at a loss how to handle the problem especially since part of the rule of the competition was the fact the three finalist dances would be presented at the closing ceremony to the public.

On Saturday morning, the organisers convened a meeting of all the artistes and journalists at which they attempted to explain the position of the government. Emotions were overflowing with some artistes suggesting that the entire body of participating artistes boycott the ceremony out of solidarity with the Mozambicans.

The choreographer of the nude show, Augusto Cuvilas was unnecessarily elevated to an issue, even when many people at the meeting said the show should be ignored, he boasted that he would not amend the offensive aspects of the dance as suggested by the organisers.

The debate dragged on and on with a lot of pretensions and seeming indecision by the organisers. However, Robert Lion, President of L’Association Francaise d’Action Artistique, AFAA, main sponsors of the show, said they were resolved to respect the wish of the people of Madagascar as represented by the contention of the President.

Significantly, the first place winner Dayo Liadi, and the third prize winner, the Haitian Kettyl Noel, who represented Mali, were given the honour to say if they would perform at the closing or not.

While Kettyl was ambivalent, Liadi spoke straight “We are in Madagascar and we have to respect the wish of the people. If they don’t want Mozambique’s dance, so be it; they have the right to decide on what is good for their people.

“We from Nigeria shall do the wish of the people of Madagascar who have been very supportive of our troupe; give them the honour to see us perform once more at the closing”.

And that did it. The first and third place winners performed at the grand closing at the Palais du Sport ET Art.

The Nigerian mounted the stage and did their country and profession proud once more.

This time they got a standing ovation from the Malagash cabinet members and people.

• The Burkinabes at Sanga 3

STORY OF A DANCE FEAST

ALPHONSE Tierou researcher and theoretician in Cote d’Ivoire dance, was the first to headline the campaign to free African dancers from the traditional dance yoke. He was convinced that "if dance in Africa moves forward, Africa will move too", and managed to convince others in 1992. The association ‘Afriquen Creations’ launched a programme called ‘Pour une danse africaine conterporaine’, and in 1995 the same association inaugurated the first African choreography platform in Sanga. The issues at stake for the founding fathers included how the Dance Arts could receive wide political support; how better to unite Africa, with its many different cultures and identities, than through dance, which is part of life and celebrations everywhere in Africa?

Besides this, work done in Dakar by Mudra Afriwue with Germaine Acogny from 1997 to 1982 and by pioneers such as Souleymane Koly and Rokya Kone of the Koteba Ensemble in Abidjan, were striking and Bomou Mamodou by Ki Yi Mbock, and some experiments in afro-fusion in South Africa had prepared the ground.

At the same time, France started to play host to top choreographers such as Irene Tassembedo, Germaine acogny and Koffi Koko, providing them with an ideal environment in which to work out and develop a new traditional African and modern dance movement. Also remarkable is the major role played by Mathilde Monnier, a lover of African choreography, who revealed many new talents beginning with Seydou boro and Silia sanou -- winner of Sanga in 997 and artistic director of the event in 2001 and 2003

Ever since it has been held in the Antananarivo, capital of Madagascar (1999 and 2001), this biennial event has been called Sanga - African and Indian Ocean Choreography platforms. "Sanga" means "summit" in Malagasy. Antananarivo, the ‘city of one thousand’ (so called in memory of king Andrianampoinimerina's one thousand warriors), is now firmly associated with the thousand dancers who perform on the stages of the event and round the biennale, in workshops, master classes and other dance platforms outside the competition.

The event is planned, organised and financed jointly by the association, Francaise d'action Artstique (AFAA), the Malagasy ministry of culture, the European Union and is supported by the Agency Intergovernmental de la Francophone.

What a participants, Jury Members Say of Sanga 3

Adebayo M. Liadi, choreographer, Ijo Dee (Nigeria)

I would like to explain that there is something within me that seethes like boiling water, and that something is dance. I would like the Nigerian public to know that dance is real job, and not just a pastime. In our country dancers are looked at with pity and as social outcasts. So I am taking part in this competition to show the world some idea on the incredible richness of Nigeria’s dance cultures. For me this competition is like World Cup football -- to have been selected is to be already up there among the greatest in Africa and the Indian Ocean. It might even lead to a little recognition in my country too.

Augusto Cuvilas, choreographer Projeti Cuvilas (Mozambique)

The Antananarivo platform is a must for the younger generation of choreographers who have chosen to create and see dance in new way in the African and worldwide context. First because it enables us to meet and compare our views then because this competition opens the door to an international stage that also includes Africa. One of the strong points of this event, in my view is that it enables artists to tour the African continent and to heighten the African public’s awareness of this new kind of dance. In this respect, Sanga is a major factor for a change of attitude towards dance in African society.

Personally, having already performed on these platforms as a dancer has strengthened my wish to continue along this road of modern creativity. To have been selected for this work particularly is a great opportunity for me to project the ideals of modern dance, which is often a subject of taboo in Mozambique and in most African countries.

Junaid Jemal, choreographer, Compagnie Adgna (Ethiopia)

It was Germaine Acogny who encouraged me to apply and persuaded me that I had a chance to be selected for the competition. She supported and helped me in approaching the Alliance Francaise in Addis Ababa; so I decided to have a go. Together with four Adgna dancers I worked out this piece around the subject of death. My grandfather had just died and this work which relates to Ethiopian funerary rites, was a kind of mourning and a way of overcoming my sadness. Finally, the Alliance Francaise provided me with the means to do it, including giving me a place for rehearsals and helping with costumes, and we were able to record the dance music and spoken parts of the performance in order to apply. To have been short-listed for the platform is very important for the company and for me. It's a unique opportunity to exchange ideas and meet other choreographers and see their work, and the opportunity of training during the Recontres platform is another terrific bonus for us.

Solifou Mamane, choreographer Compaignie Gabero, (Niger)

We wanted to take parts in this competition as a way of presenting the culture of Niger to an international audience; and at a personal level, to escape our obscurity and anonymity. For us Recontres is a platform to interact, know and exchange views with other artistes, and also a pre-requisite for any modern African dance company. We applied in 2001 but weren't short-listed. That taught us a lesson; so this time we worked long and hard to prepare or this festival. We also applied for a grant from the FSP (Fund de Solidarite Priortaire -- mutual aid fund) and used the money for the sole purpose of preparing for this competition. To have been short-listed this time shows that we are on the way to becoming a professional group.

Hycinthe Abdoulaye Tobio, choreographer, Les Jeunes Tresaux (Chad)

My country, Chad had no previous history of modern dance. That was because of the lack of exchanges, experience and training for choreographers. Many Chadian companies that experimented with modern dance were stuck with the label ‘folk dance’. That's why I began a search for new forms of expression; which led me to Germaine Acogny's International Centre for Dance and choreography; and this opened my way and brought me in touch with this competition. I then worked very hard to be short-listed as one of the 10 finalists at the 4th Recontres platform two years ago, and I came fourth.

Auguste Wilfried Oudraogo, Choreographer TA, (Burkina Faso)

Reencounters is a great platform for companies from Africa and the Indian Ocean that also welcomes artistes from other continents. We are taking part to just for the competition but to have opportunity to interact with fellow dancers and choreographers on an international stage; we worked very hard, however, to prepare for the competition.

AND WHAT MEMBERS OF THE JURY SAY:

Aimee Razafimahaleo, Professor of dance at Antananarivo University and member of the jury

Sanga has become an essential event, for upcoming dancers as well as the established ones. Africa and the states of the Indian Ocean can be proud of these Reencounters platforms in Antananarivo. I hope that my presence on this international jury may give new impetus to dance in all its forms in Madagascar. One of my dreams would be to set up a choreographic training course together with French speaking organisations in order to open a National School of Dance in Madagascar.

Sophiotou Kossoko, Choreographer

The only question is how can I meet the expectations of the choreographers and dancers who have been selected? I will be looking at their work through the eyes of my own experience, which is that of an African woman, living in France, and brought up at the crossroads of different cultures. Apart from the competition itself, the event in my view, is above all, a meeting of artists. I want to be there to listen, exchange views and take part in an open discussion on the essentials of creative work.

Diana Boucher, Consultant programmer at the Perreault foundation in Montreal

Africa must be one place where choreographers experiment the most creatively with new dance movements and invest new codes. That dance is so deeply rooted in African culture is certainly one of the reasons for this. Contemporary African choreographers, an unknown entity a few years ago, now mix with their peers from other continents and are in contact with other ways of doing things. The Renecontres African and Indian Ocean Choreograhic platform has greatly contributed to promoting modern African dance at an international level.

IJODEE, NIGERIAN TROUPE, WOWS THEM AT INTERNATIONAL DANCE MEETS

Mihari, the pretty hostess attached to the Nigerian troupe at the on-going Sanga 3, the international festival of choreography and dance, holding in Madagascar, waved excitedly at Dayo and said "no kain". She followed it up with a generous smile, which no doubt suggested she was happy with herself

She has caught the bug just like all the rest of her fellow Malagasy and participants at the festival who have since adopted the seven-man Nigerian troupe as some kind of folk heroes.

Here in Antananarivo, the Madagascar capital where the festival --the fifth edition of the African and Indian Ocean Choreography Platform -- is holding , almost every other person wants to learn and speak the Nigerian pidgin English. "They love our pidgin so much and they want us to teach them; they compare it to the patua of the Jamaicans… but they are even more surprised when we told them that it was the inventions of the Nigerians", stated Victor Eze, the administrator (manager of the Nigerian team)

And almost every other person, particularly among the participants, want to be in the midst of the Nigerians. They think that the best place to catch unrestricted fun is right there in the camp of the Nigerians.

Indeed, the Nigerians are the cheer-leader at this dance feast. They are the one to lead at the various interactive sessions -- these are gyration- like informal gatherings held every night at the Soarono Station , a currently disused train station which serves as the dining centre for the almost 2,000 participants from around Africa and the Indian Ocean .

Once the band launched the music, usually the first set of dancers to be on the floor is sure to be the Nigerians. They translate the Malagasy music into the Nigerian local dance icons – Ekombi, Bata, Koroso and so on.

Perhaps, only the Senegalese get to beat the Nigerians to the dance floor . But even the West African neighbours can’t match the upbeat groove of the homeboys. At this festival the crowd just loves the Nigerians; and can’t seem to get enough of them.

"Your people are so free and happy; I love their spirits", stated Stephen Ochalla, artistic director of Kwoto Art Centre, who is representing Sudan at the festival. "There is so much confidence in the Nigerians; and they dance well. I can’t wait to see their show", stated the dark, gangling Sudanese.

"I know that the first prize is for us. I can feel it, even from the feelers that one gets from other participants, it is sure that we have something unique to offer; and everybody thinks highly of our team", boasted Eze, himself an experienced actor and dancer who toured Europe extensively with cast of Wole Soyinka’s King Baabu.

Nigeria’s representatives at the festival is Ijodee Dance Company, a troupe of seven led by Adebayo Muslim Liadi.

Ijodee is not in Madagascar on Nigerian government’s sponsorship but it had been facilitated to the festival by the French Cultural Centre, Lagos. The centre under the leadership of Joel Bertrand had organised a competiton through its no yearly ‘Dance meets Danse’ programme that featured local troupes at is Kingsway Ikoyi Road premises last August.

Ijodee came top. Their prize is the current engagement; to represent Nigeria at the fifth African and Indian Ocean Choreographic Platform which began on Saturday and will end November 15.

The festival dreamt as far back as 1992 had begun in Luanda at which Omitun, the Ibadan-based troupe came fourth. But since the French choreographer, Salia Sanou won the First Prize in 1997, the festival has shifted its base to Anatananarivo, capital city of Madagascar, which then hosted it in 1999 and 2001 with Sanou as Artistic Director. This is the third edition And things are looking up, pretty well, for the Nigerian chaps.

At their workout on Monday morning at the Albert Camus Cultural Centre, right in the centre of the city, Ijodee cast and crew were in great spirit. No one who had seen them during the dinner and the gyration the previous night at the Soarano Station would probably believe they were the same fun makers. They were in the serious business in the work-out with the team’s leader, diminutive Liadi in charge of the muscle – stretching exercises. Saidi Ilelaboye, who doubles as the musician (drummer) and Technical Director, was sweating it out with the Centre’s technicians to set the stage for the team’s technical rehearsals billed for later in the day.

Their first show was yesterday when Liadi did his solo at the Theatre Isotry in another part of the city, where on Monday night, the South African duo of Solo Pesa and Valerie Berger had a three-in-one stupefying show that drew a standing ovation.

Liaidi’s Ido Olofin, a robust ritual of cultural rediscovery, pulled a successful shot yesterday. This was clear from the response of the audience. He hardly could walk out of theatre free as captive troupe of fans and admirers encircled his feet -- those same little muscular feet that had moved as if possessed of the spirit of a grinding machine.

There is already a call for Ido Olofin encore. Tonight, the competition section of the festival begins and Ijodee company is offering Ori (The Head), which Liadi explains as a spirit linked to power of artistic intuition

Adebayo Liadi, a graduate of Senegal International Centre for Dance and Choreography says, "I use traditional dance and music as source of imagination or as a glossary of composition. The choreography leaves its root and returns to them just as it feeds on a variety of influences an styles without ever letting itself be misled. It draws from these languages to create something decidedly unique".

Ijodee Dance Company founded in 1998 is only one of the 11 companies elected from 82 (from 32 countries) that applied to participate in the festival. Aside of Nigeria, there are also Ethiopia; Senegal, South Africa, Niger, Mali, Chad, Egypt, Mozambique; Cape Verde and Burkina Faso.

Back to Eze, the articulate administrator of the Nigerian team, who himself has become a star participant at the festival’s Administrator Workshop based on the quality of his contributors to the discussions.

The festival, he says, is an eye-opener to the many possibilities and potentials of the Nigerian dance artiste and culture industry in general.

"We are yet to perform, yet there is so much respect for us. There is even fear that these Nigerians will do wonders. I wish they know that back at home, the dance artiste and the artiste in general is a nonentity to our government and the public in general".

Sanga 3 is organised by Association Francaise d’Action Artistique (AFAA) and National Office of Arts and Culture Madagascar (OFNAC) with supports from the Madagascar Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European Union Delegation to Madagascar and Intergovernmental Agency of French Speaking Nations

IJODEE, NIGERIAN DANCERS, CAME TOP AT FESTIVAL IN MADAGASCAR

In Madagascar, right in the middle of the Indian Ocean, the name of Nigeria is on the lips of many people. The country’s representatives at the fifth African and Indian Ocean Choreography festival, IjoDee Dance Company came first ahead of 10 other troupes that competed for the grand prize.

The seven-man IjoDee Company had presented its contemporary dance creation entitled Ori (The Head) on Wednesday and the 11-man jury headed by the Ethiopian film maker, Abderhamane Sissako, thought it had the best package as far as the criteria for the competition go.

According to Sissako, the Nigerian won the first prize because they were "original, sincere and sensitive to their culture and the language of modern dance". Besides, he added, "they were very professional in their approach and, inventive."

Trailing Nigeria in the second and third places were Mozambique and Mali. Adedayo Muslim Liadi, leader of the Nigerian troupe and the choreographer whose feat had suddenly made him the toast of the over 2,000 participants from Europe, American, Africa and the Indian Ocean, was overjoyed at the achievement. He kept screaming, "I give thanks to God the almighty for his blessings and gift of life. I thank him for the strength he gave me and my dancers, and the talent and skill he has endowed me with."

Asked how he felt at winning the prize, Liadi said, before the announcement, "I was tensed because I did not know what might happen. But I had seen it already that God was going to do wonders in my life this year. I felt it and now it has happened. I give all the glory to God and to my people back in Nigeria who have always given me support. I thank the French Cultural Centre for their support all the time and to come here.

"I thank the Nigerian artists’ community too because this glory is for all of us. It is tonic for us to do all the best that we can do. The world is there for us all if only we try hard and believe in ourselves and our culture"

Liadi’s Ijodee had come top at a competition organized among about 20 Nigerian dance troupes by the French Cultural through its yearly Dance meets Danse programme held last July at its Aromire (former Kingsway Road) Street, Ikoyi Lagos premises.

On the factors he thought could have given his company the topmost prize ahead of the other contestants, Liadi said; "One is originality; yeah originality; because I refuse to leave my root; I refused to get out of where I come from. And that is a lesson for all of us African artistes. Don’t ever leave your root. Never. Always tap from it and build on it; because its yours."

The diminutive choreographer continued: "if you watch all the other groups that contested, they were very good -- good movement, good form, but the problem was too much of European stuff. But all my movements are from Africa… from swange (Benue), Bata (Yoruba), Koroso (Hausa), Atlogwu (Ibo), Ekombi, (Cross Rivers) and even from Senegal, Benin Republic, Mali…all of them .. I refused to get out of my Africanity. I am going to retain it because it has paid me today and it will surely pay me everyday; I am sure."

Also, Liadi thinks that his feat will now open up a world of opportunity for Nigerian dancers and artistes in general. "I know that thousands of Nigerian dancers will have people from all over the world coming to them.

"There are a lot of scouts here who have seen what we are able to do with our arts and I am sure they will all want to explore Nigeria further."

For the Nigerian culture sector, Liadi feels that this feat which is "like winning the top prize at the dance olympics should make our government to recognise the importance of culture in world politics".

For their feat, Ijo Dee Dance Company formed in 1998, has earned the opportunity to tour Germany, Belgium, France, London, Spain, Tunisia and Italy between February 28 and May 7 next year. And in 2005, it will do an extensive tour of Africa. The tours are the dreams of every professional dance companies.

The biennial festival had begun in 1995 in Luanda but the last three editions since 1999 (and including the current edition) have been held in Antananarivo, the Madagascar capital city

WHEN DANCE RULED THE INDIAN OCEAN WAVE

MADAGASCAR, the beautiful country located on the Indian Ocean, has made name for itself as host of a most important cultural programme for the blacks and African world. Since 1999 when it decided to host the African and Indian Ocean Dance Platforms, the country of 16 million people has, no doubt, wormed itself into the hearts of dancers and choreographers as well as patrons of the art from around the world.

And for tourists with penchant for the physico-emotional performance art, the dance festival is gradually becoming a biennial pilgrimage. They troop in every season to have had a full feasting on the choreographic art as well as on the various crafts of the people of the country.

The government of the country must have been sufficiently informed by certain progressive and divine vision to have convinced the main promoters of the project, the AFAA (Association Francaise d’Action Artistique or French Association for artistic Actions), to move the dance programme to their land.

This year, between November 7 and 15, that the country hosted the festival, it played host to an estimated 2,000 visitors, including the over 300 participants from about 20 countries on the continent of Africa.

There were also guests from the United Kingdom, United States of America, The Netherlands, Germany, Latin and South America as well as from Asia. These included scouts who came to shop for dancers, choreographers and programmes for their various festivals and art centres; tourists; and experts who functioned in the festival as officials, members of the jury among others.

It was the third time Madagascar would be staging the festival hence the acronym, Sanga 3, and its success must have satiated the country's leaders who declared at the closing ceremony that their people had come to see the platform as part of their national heritage.

Madagascar's Culture minister, Odette Rahaingosa, indeed, said plans had already begun in earnest for the next edition in 2005. She noted the development, which the festival had brought to the professional activities of the country's performing artists. Since 1999, she said, many more professional dance groups have emerged on the Malagasy stage and; the fortunes of artistes in general have improved immensely.

And though the minister, on behalf of the country's government, had reason to quarrel with certain aspects of the festival, like the dance presentations of the Mozambiques, Projetos Cuvilas, in the competition category -- in which five adult ladies were paraded nude for about 20 minutes -- she still welcome a continuation of the festival in the country.

The artistic director of the festival, the Burkinabe Salia Sanou, also acknowledged the fact that the platform has indeed found a home in Madagascar. Sanou, himself, the 1997 winner of the festival's grand prize, had started his directorial work on the Sanga with the 1999 edition, which was the first for the country.

In reviewing the 2001 edition, he said: "I think Sanga 2 turned out very well, and when one considers the number of applicants for the event this year (2003), one can only take satisfaction in the success of this competition that created more and more interest from dances and choreographers who want to experiment with other ways of creating, to revitalise the art of choreography and to express themselves."

There was an unprecedented 82 applications for this year's festival competition, out of which only 11 were eventually chosen. This attests to the growing importance of the Platform.

Sanou explains that the selection of the 11 finalists -- out which Nigeria's Ijodee emerged the first prize winner -- was done by a jury composed mostly of the younger generation of dancers, all of whom had taken part in the festival in the past.

These jury members included Opiyo Okasch (who was recently in Nigeria for a workshop as a guest of the French Cultural Centre), Faustin Linyekula, Seydou Boro, Patrick Acogny. There were also Africans from the Diaspora such as Georges Momboye.

Speaking specifically on the strong points of Sanga 3, unassuming Sanou, who throughout the event appeared no more than like any other guest at the event, said: "Well, of course, the competition itself, for which the finalists are working hard to prepare, but also the 'Let's dance' platform, which really is a strong point insofar as it brings this art to a wider audience, and in particular a Malagasy audience.

"This platform also makes it possible to relieve the stress of the competition, because the entrants can perform freely, not under the gaze of the jury, but in front of an appreciative audience. Moreover, a programme has been set up that is a springboard for young choreographers and that covers a fairly complete spectrum of choreographic creativity in Africa and the Indian Ocean.

"Finally, the time devoted to exchanging information and experiences provided by the training schemes are a very important aspect of this platform. All these events form a whole, the various different centres formed by the competition, the programming, opportunities for exchange such as the round tables, all complement one another and make it possible to raise standards every two years.

As a result of the recurrent problems engendered by the competition aspects of the festival, including the obvious and sometimes exuberant, struggle for the prize by the dance companies at the expense of true artistic productivity, there had been call for a cancellation of the competitive programmes in the Sanga. But Sanou, says: "In the beginning it was impossible to do anything other than a competition, because there were not enough African companies to create a strong programme. This time 82 companies have applied. That is no mean thing. Next year, there may be as many as 150. A lot of high quality choreographers have emerged, and gradually the context of a competition will become obsolete and it will be possible to organise an attractive, large scale festival that will give more exposure to African and Indian Ocean modern dance in the long term than could be done by a competition.

Sanou is particularly happy that through the platform, a new work of choreographers is emerging on the African continent.

"This movement has made it possible to raise real questions about working environments and conditions. I think that the infrastructure being built will also enable Rencontres (Sanga) to rise to another level, as with better working conditions, more venues open to dance and more research facilities, we are going to see more and more high quality performances.

Interestingly, rather than the usual prize money always given to winners of art festivals, Sanga has come up with a more productive reward, which at least, will keep the companies working in the future. The prize money that had been awarded to the first three winners has been replaced by an international tour and Sanou, who was instrumental to the new decision, says this would remain a continual policy.

He says: "I have always thought that the jury's decision ought to be rewarded by more than just a sum of money, and that the prize should serve to encourage and help the winning company to develop. That is why an extensive tour must be one of the finest presents one could give the winners.

"A tour certainly enables a company to gain recognition, but beyond that consideration, it shows the company that the work it did is of value. This also helps to structure the winning companies, because the more they tour, the more experience they acquire in artistic and administrative matters.

"A tour bonds the team and helps it to project itself into the future. It forces companies to organise themselves. One must not forget that most applicants come to the competition with no administrative experience. This prize is therefore a real help to the companies in structure and planning.

How IjoDee, Nigerian Troupe got the green in Madagascar

On a day degenerate art seemed to rule the soul of the dancer’s stage, dance steeped in swift, dynamic and melodic riff etched the Nigerian dancers in the heart of the international audience that sat mesmerized in the Alber Camus Theatre on L’Independent Street on Wednesday night.

While the Egyptians mounted a pop art that oscillated between pantomime and agit-prop and the Mozambicans paraded starkly naked maidens in wild, spasmodic and erotic steps and the Chadians did a dance drama with semi-nude characters, the Nigerians did the real dance of the night and got the audience clapping and clamouring for more, long after the 30 minutes duration of the act had lapsed.

The three other shows indeed, confounded critics and discerning members of the audience on the direction of so-called contemporary modern art. And it is not impossible that the open display of naked bums and boobs by the Mozambicans, and the balls by the Chadians must have offended moral sensibility of the elite audience many of whom came with their children.

The Nigerians gave the delight as they engaged their feet and supple bodies in poetic flight into the world of rituals to tell the story or Ori (The Head) or Destiny. Though there were some incoherent movements and gestures here and there and, a problematic technical input nearly ruined the smoothness of the show, the jury and the audience made up of co-participants in the festival and other select mmbers of the public, thumbed up the Nigerian how.

• Dayo Liadi

The presentation by IjoDee was an intensely expressive piece of dance that also gave ample room to drama and pantomime. The music of Ori, contrary to the weird assemblage of sounds that obtained in some of the other works presented throughout the competition, also relied heavily on evocative melody, inventive chants and layers of cross-border musical inflections, to express the mysteries of life and the beat of man’s journey through life in the hands of unknown forces encapsulated in the unseen character called Ori.

Prior to the last Wednesday show and, in fact, since November 8, beginning of the eight-day 5th African and Indian Ocean Choreographers Platforms in Antananarivo, the capital city of Madagascar, IjoDee Dance Company’s members had been held as some sort of celebrities.

They were popular. Immensely beloved.

Everyone seemed to have bought into them.

And the fame had nothing to do with the usual Naija-for-show, the notorious boisterousness of character easily discernible in the style and carriage of an average Nigerian person.

The warmth shown the Nigerians had nothing to do with the fact that the seven-man IjoDee had its own exuberances and, was loud with a bit of nuisance traits in carriage. That was expected of course of a team of very young cast, which with exception of the team leader, the manager and the technical director, were having their very first exposure on an international stage. The love had so much to do with the quality of work expected from the team.

The over 2,000 participants in the festival from about 18 countries had a mindset of reverence for the Nigerians. Much of it had to do with the record of the team-leader, Adedayo Muslim Liadi, who indeed has done quite a good work moving around in the European dance circuit. Having worked in Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels and then pounded the African circuit well, his reputation seemed to have preceded him at this biennial dance meet named Sanga 3 – the third in the Madagascar capital city since 1999.

Even the chief dreamers of the project, unassuming French choreographer Salia Sanou (artistic director of the festival) and Senegalese Germaine Acoigny, appeared to have rested much hope in Liadi to set a fresh agenda for an emergent African choreographic vocabulary, which no doubt, is an underlying agenda of the festival.

In fact, shortly after the show -- at the interactive session usually mounted every night in the disused Soarano train station -- an excited Acoigny sprinted to the table where the IjoDee cast and crew sat swimming in the admiration of their fellow artists, pulled Liadi up and gave him a rounded hug:

‘You have done me proud. I am very happy with you”, she said in her Frenchised English. Then turning to other members of the team, she sang,” You have done very well all of you. We are all very happy with you. Good job all of you.”

And next, in motherly gesture, she cuddled Nneka Celina Umeigbo, the only female member of the team, saying: “but she is the best… you are all very good but the girl is the best. You see what the woman can do? Everything that a man does, the woman does it well, so she is the best”

By now the whole house seemed to have directed its attention to the table. Perhaps it was Acoigny’s deep bass that fills the house even when she speaks softly. Perhaps it was the mood carried over by the crowd from the Albert Camus Theatre… they just couldn’t stop discussing the Nigerians, even after the jamboree of boobs and balls by the Mozambicans and the Chadians, had faded into insignificance.

• Ijo Dee in performance

Soon, the brief motherly affection by Acoigny launched a sort of pilgrimage to the glistening aluminum-cast dining table where the IjoDee cast and crew sat. Especially, the score of journalists from Europe, the United States, Canada and Britain wanted to know what made these chaps from West Africa so thick and confident.

Acoigny, first director of the famous Senegal International Centre for Dance, is revered in the African (and French) dancers’ circuit as a matriarch of the choreographic art. Liadi had been opportune to train under her in Senegal school -- which is however, unfortunately, currently shut down due to paucity of fund. Her attestation to the quality of the Nigerians’ show was an endorsement of some sort.

Stephen Ochalla, the only choreographer from Sudan who flew in from a 10-month Residency programme at a dance institute in Amsterdam in The Netherlands, sat next to Liadi and his excited team; he shook his head and declared: “ These Nigerians have won, I am sure”

But noticing the incredulous look on the face of a reporter, also at the table, he asked: “You don’t believe me? You will see. They are the only one that really danced on stage. The others were doing movements and sports and seemed confused about the meaning of contemporary modern dance. But the Nigerians, they understand modern dance very well and they have not lost their identities like the others”

Since the beginning of the festival, Ochalla, artistic director of Kwoto Dance Institut in Khartoum, had been deeply worried about the direction of the contemporary African dance, as reflected in the various presentations of the about 11 competing companies and 12 other soloists at the festival.

Between himself and the Zambian Georges Daka of Zuba ni Moto Dance Ensemble, (who was also featuring in the non-competitive solo choreography events), they had had countless informal seminars on the emerging submersion of the identity of the African dance in the, according to Daka -- ‘new madness called contemporary modern dance’. They felt uncomfortable as they saw their fellow African dancers and choreographers deliberately committing what could be termed ‘cultural suicide’ just so to speak the dance language of Europe and the West.

The two artistes, mature and (no doubt) idealistic, saw the dawning of a dangerous trend in which, in no time, the African dance artiste would have been stripped of his own cultural philosophy; the very essential that ought to define, at least, the content of his art.

“Our dancers are trying too much to be Europeans, they forget that African art must be rooted in the ideas of the people. This is dangerous”, an exasperated Ochalla sighed.

Daka contextualised the trend in the long-drawn struggle between the West and the rest of the world, already enunciated in the undercurrents of globalisation… “This looks like another scheme to strip Africa of its identity and make us speak like the colonisers. It seems that Europe wants to kill what is ours and then make us take only that which is theirs”

“Really, I don’t see much dancing in what our people are doing at this festival. We have to be worried that all they are doing is just moving and expressing forms without dancing. We have to be very worried about that; about the future of dance in our continent and how our people will relate to most of what our boys are doing now”

Continued Daka, “It is good to learn the skill of creating new forms and techniques from Europe but we must always return to the root of our dance art”.

Ijo Dee on duty.. in Madagascar

Interestingly, Daka seemed to have been speaking to the conviction of Adedayo Muslim Liadi, the Nigerian representative at the festival.

The festival programme note celebrates Liadi’s choreographic virtues as the ability to take off from his cultural root, take a wide flight into the fairy-like space of the West with all its fleeting characteristics and then return to the very earth that nurtured the vision and imagination at the onset.

Stated the note: “The choreography leaves its roots and returns to them, just as it feeds on a variety of influences and languages to create something decidedly unique”.

Liadi indeed, had hinted of his mission as a choreographer on Tuesday at the downtown Isotry Theatre when he gave his non-competitive solo show. He presented Ido Olofin, a ritual enunciation of the travails of modern man who in the lust for acquisition of impurities and imperfections, has lost the ability to interrogate the essence of his existence and nurse the origin of his being.

The choreographer offers in the piece rebirth rite as not an option but a necessity for atonement and spiritual regeneration. After a season of trials, drought and spiritual dislocation, an appropriate propitiation will bring the rains and the greens; he suggests.

But in the solo show that lasted 20 minutes, Liadi traversed and as well criss-crossed the many cultural boundaries of geographical Nigeria. He did this in a lot of colours, movements and graceful steps. These virtues he also brought to bear in the group show, Ori. And these were the virtues that wormed the Nigerians into the heart of the audience on Wednesday

Out of the seven groups that had featured, as at Thursday, in the competitive category, IjoDee stands in a class of its own. It is perhaps only the South Africans that have come close in terms of dynamics of expression in which there is symphony between content, form and techniques. The rest have been laying emphasis on either one or two of the characteristics of a complete choreography.

• The Mali troupe at Sanga 3

• The Mali troupe at Sanga 3Instructively, while the African dancers, in their obviously unformed and confused voices, struggle to speak western choreographic vocabulary, Valerie Berger, the French choreographer-dancer presented a show that was steeped in African rhythmic culture. She reached deep into the African cultural materials and set same in the context of modern forms and techniques and passed her message easily in Cornered and Lucy, which she presented on Monday. This was not the case with the South African Sello Pesa, her sparing partner who seemed lost in the wilderness of identity; just like many of his comrades from the continent.

Back to the Mozambicans:

The show discomforted the government of the host country, Madagascar that the President insisted that the ‘nude dancers’ must not be allowed to present the dance at the closing ceremony.

The President said his Minister of Culture had told him that the dance was offensive to public morality.

The organisers were at a loss how to handle the problem especially since part of the rule of the competition was the fact the three finalist dances would be presented at the closing ceremony to the public.

On Saturday morning, the organisers convened a meeting of all the artistes and journalists at which they attempted to explain the position of the government. Emotions were overflowing with some artistes suggesting that the entire body of participating artistes boycott the ceremony out of solidarity with the Mozambicans.

The choreographer of the nude show, Augusto Cuvilas was unnecessarily elevated to an issue, even when many people at the meeting said the show should be ignored, he boasted that he would not amend the offensive aspects of the dance as suggested by the organisers.

The debate dragged on and on with a lot of pretensions and seeming indecision by the organisers. However, Robert Lion, President of L’Association Francaise d’Action Artistique, AFAA, main sponsors of the show, said they were resolved to respect the wish of the people of Madagascar as represented by the contention of the President.

Significantly, the first place winner Dayo Liadi, and the third prize winner, the Haitian Kettyl Noel, who represented Mali, were given the honour to say if they would perform at the closing or not.

While Kettyl was ambivalent, Liadi spoke straight “We are in Madagascar and we have to respect the wish of the people. If they don’t want Mozambique’s dance, so be it; they have the right to decide on what is good for their people.

“We from Nigeria shall do the wish of the people of Madagascar who have been very supportive of our troupe; give them the honour to see us perform once more at the closing”.

And that did it. The first and third place winners performed at the grand closing at the Palais du Sport ET Art.

The Nigerian mounted the stage and did their country and profession proud once more.

This time they got a standing ovation from the Malagash cabinet members and people.

• The Burkinabes at Sanga 3

STORY OF A DANCE FEAST

ALPHONSE Tierou researcher and theoretician in Cote d’Ivoire dance, was the first to headline the campaign to free African dancers from the traditional dance yoke. He was convinced that "if dance in Africa moves forward, Africa will move too", and managed to convince others in 1992. The association ‘Afriquen Creations’ launched a programme called ‘Pour une danse africaine conterporaine’, and in 1995 the same association inaugurated the first African choreography platform in Sanga. The issues at stake for the founding fathers included how the Dance Arts could receive wide political support; how better to unite Africa, with its many different cultures and identities, than through dance, which is part of life and celebrations everywhere in Africa?

Besides this, work done in Dakar by Mudra Afriwue with Germaine Acogny from 1997 to 1982 and by pioneers such as Souleymane Koly and Rokya Kone of the Koteba Ensemble in Abidjan, were striking and Bomou Mamodou by Ki Yi Mbock, and some experiments in afro-fusion in South Africa had prepared the ground.

At the same time, France started to play host to top choreographers such as Irene Tassembedo, Germaine acogny and Koffi Koko, providing them with an ideal environment in which to work out and develop a new traditional African and modern dance movement. Also remarkable is the major role played by Mathilde Monnier, a lover of African choreography, who revealed many new talents beginning with Seydou boro and Silia sanou -- winner of Sanga in 997 and artistic director of the event in 2001 and 2003

Ever since it has been held in the Antananarivo, capital of Madagascar (1999 and 2001), this biennial event has been called Sanga - African and Indian Ocean Choreography platforms. "Sanga" means "summit" in Malagasy. Antananarivo, the ‘city of one thousand’ (so called in memory of king Andrianampoinimerina's one thousand warriors), is now firmly associated with the thousand dancers who perform on the stages of the event and round the biennale, in workshops, master classes and other dance platforms outside the competition.

The event is planned, organised and financed jointly by the association, Francaise d'action Artstique (AFAA), the Malagasy ministry of culture, the European Union and is supported by the Agency Intergovernmental de la Francophone.

What a participants, Jury Members Say of Sanga 3

Adebayo M. Liadi, choreographer, Ijo Dee (Nigeria)

I would like to explain that there is something within me that seethes like boiling water, and that something is dance. I would like the Nigerian public to know that dance is real job, and not just a pastime. In our country dancers are looked at with pity and as social outcasts. So I am taking part in this competition to show the world some idea on the incredible richness of Nigeria’s dance cultures. For me this competition is like World Cup football -- to have been selected is to be already up there among the greatest in Africa and the Indian Ocean. It might even lead to a little recognition in my country too.

Augusto Cuvilas, choreographer Projeti Cuvilas (Mozambique)

The Antananarivo platform is a must for the younger generation of choreographers who have chosen to create and see dance in new way in the African and worldwide context. First because it enables us to meet and compare our views then because this competition opens the door to an international stage that also includes Africa. One of the strong points of this event, in my view is that it enables artists to tour the African continent and to heighten the African public’s awareness of this new kind of dance. In this respect, Sanga is a major factor for a change of attitude towards dance in African society.