7th Gwanju Calls... Remembering 2004

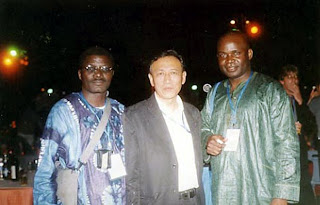

• Osifuye with Yong Woo Lee (artistic Director of Gwanju Biennale, and jahman Anikulapo on the ex hibition ground

The 7th Gwangju Biennale, will be directed by the – to use the cliché – Nigeria-born America-claimed Okwui Enwezor, who has made tremendous impact around global art circuit as Curator and Art Director of mega shows, including the Documenta in Kasel, Germany.

The show is slated to open on September 5, 2008, and could run for about six months or more drawing thousands of visitors in its first few weeks of staging and subsequently still attracting visitors from all over Asia and tourists from the West and Europe.

Gwanju Biennale is the mega art show in the deceptively rural-faced Gwanju city, way off the techie capital of South Korea, Seoul. Though not as big and influential as the Documenta I Germany, or the Venice Biennale or the Sao Paulo Biennnale and others in their class and status, the Gwanju Biennale is about the most emotive and grossly evocative of the struggle of man from liberty from political, social and economic conditionings that prevent him from realising his full humanity.

Gwanju is acknowledged as “the spiritual center in the struggle for democracy in Korea”, taking its character from an eventful but painful event that occurred in the 80s when the state instrument of force descended on a group of students protesting certain odds in the political system and massacred them.

•Taking a ride in the bus with other participants

•Taking a ride in the bus with other participantsThus in 1995 when Gwangju Biennale birthed, it was as response “to the critical impact of the democracy movements of the 1980s and the influence of emergent forums of civil society on contemporary Korean experience”, according to the website of the art show. It continued: “Since its founding, the Gwangju Biennale has established itself as one of the leading large scale global exhibitions and a pioneer in curatorial experiment in the field of contemporary art”.

In the sixth edition held in 2004, and directed by New York-based Korean Curator YungWoo Lee, Nigeria had a voice at the show, represented by the Photographer, Muyiwa Osifuye who presented his collections of documentaries of the living cultures of the famous Oko Baba settlement on the bank of the Lagos lagoon, which itself has become a sort of a legendary theme in artistic representation. The West Africa section of the show had been curated by US-based Nigeria art historian/curator Chika Okeke, who also featured the sculpture El-Anatsui. The Curator against the grain.

The theme was ‘A Grain of Dust’: ‘'Little Drop of Water'’ and it featured a revolutionary dimension to curatorship when the artistic Director Lee introduced the idea of Viewer-Participants — a concept which -- in summation -- ensured that a select representatives of the viewing public of art had a say in the conception (even if marginally) and presentation of the final work on display at the grand biennale. It involved the group of carefully-selected V-Ps working with the artist from the conception of the work to the execution and the final presentation. The V-Ps included people of varied professional callings, faith and social classes, thus there were teachers, farmers, journalists, engineers, housewives, students etc etc.

The stem of relationship between the two poles was formularized in such a way that even though the Artist was to work with the V-P, the latter was not expected to be an intruder in the creative process. Not even his suggestion was suggested a compulsory consideration for the artist. The prerogative of the creative process remained an exclusive right of the artist but if he/she wished he could allow the V-P a say in any of the stages of the creative experience.

I was the V-P for the photographs of the Nigerian photo-Artist, Osifuye. And this has remained a life-time experience for me as would be shown in the report below.

• A taste of Korean luxury in the hotel by the water

DRAFT LITERATURE FOR GWANGJU BIENNALE, 2004

BY JAHMAN ANIKULAPO

IDEA ABOUT ART

There are populist artists and there are visionary artists, just as there are populist politicians and philosopher politicians.

The populist artist is the more popular because he appeals to the basal instincts, more to the brawn and purse, the dancing feet and sexual desires of the audience. The Artist-philosopher steals the soul of his audience with his words, movement of his figures and motives, or performance. He conquers the audience's space of reasoning; he imprisons his emotions and overrides his cerebral cavity so much that he falls in line with his thought process. That is the artist that moves men to positive actions and speed up the process of change. He is a medium of national reformation or cultural regeneration. He is the one to spur a renaissance in the social consciousness.

INTERACTION WITH THE ARTIST

Three 'Dialogue' sessions were held between the artist and myself in the course of his preparing for the Gwangju Biennale. But these sessions are outside of the countless telephone conversations between us as well as several exchanges of ideas via the emails.

Fortunately, I had been familiar in the past with the photography of Mr. Muyiwa Osifuye. I had written on his works in the past as an Arts Reporter (as well as edited reports on his exhibitions and interviews), for ‘The Guardian’ newspaper, where I work currently as the Editor of the Sunday publication. This familiarity aided the cause of our interaction and consequent dialogue on his portfolio for the Gwangju Biennale.

However, in our discursive session, we adopted the exploratory mode of interrogating the images, to unearth the underlying artistic contentions. I deployed my reportorial skill to probe the mind of the artists. The result was marvelous as the artist, I believe, opened up in explaining his works. I believe we achieved a lot in our three dialogue sessions, and the other non-physical contacts.

The first session was to understand the theme of the Biennale. The second was to rub minds on our individual contentions about art. The third was the exploratory i.e interrogating the artist and his objectives for the Biennale as reflected through his portfolio.

I was very conscious of not turning up an intruder in the artist's creative process, including his visioning process. I wanted very much to distance myself from the thought process that informed the choice images. However, through our interaction, I have been able to learn a lot about the process of photo-documenting vital sectors of the society. I only hope I hadn't mounted an unnecessary interference in the artist’s creative endeavour.

From the study of Muyiwa Osifuye's Gwangju portfolio, four basic concepts emerged -- as agreed during the third session of the Dialogue between the Artist and the Viewer-Participant:

1. DUALISM OF HUMAN EXPERIENCES

Dualism of experience of the people, informed by social and economic stratification in the society. In other words, there could be affluence and impoverishment existing within same social plane or habitational space. The palpable tension imminent in such an intercourse of desires and goals are subdued but emphatic in the distrust, frictions and mutual suspicion that would naturally underline the relationship between the classes. But the dualism as enunciated in the current portfolio is not just about plane and spaces, it is also discernible in human gestures and body moves, in human psychological relationship with his immediate surroundings, among others.

Some of the images depict the intercourse of the classes — social and economical — as reflected in the type of structural facilities available to each class.

Some other images show the intercourse between the environments. Beneath the composition of the pictures is the inevitable friction of intentions and desires of the occupiers of the divergent environments. The grossly deprived and the excessively affluent will naturally harbour mutual distrust, which could unsettle the social balancing and keep the system perpetually in discomfort.

2. CHAINED DREAM (TOMORROW):

An imagistic re-presentation of the in-conducive environment in which children are forced to get education are presented in some of the images. In such slums and environmentally-violent settings, the quality of education is suspect. Yet, the parents of the children insist that their wards must be educated; they desire that education will lift their coming generation out of the abyss of reject into which they had been dumped. They realise they had been wasted, but insist that their children must not suffer same fatalistic fortune. That is why they ensure that some degree of formal and informal education are imparted in the children; the bad environment notwithstanding.

But there is a greater danger. The children nurtured in that suspect learning environments are expected to compete in the larger social, political and economic spaces with the privileged children from the well-equipped schools. The future is indeed intriguing. More dangerous is the fact that the deprived children are aware or are conscious of the silver linings on the other side.

This is the "Chained Tomorrow", instigated by the chained dreams of today. This perhaps is the essence of the artistic vision, when images of deprivation and affluence are juxtaposed in same frame of picture.

There is also the subtle sub-theme of 'light in the midst of darkness; which is essentially an extension of the fundamental message in majority of the pictures. The sparks of life (light) even in the depth of despair (darkness) in the ghettos and slums, are symbolic of a future blistered of humanistic principles of fulfillment and contentment. Anytime the dust (the deprived) aspires to the exclusive properties (snooker, TV, Radio, fast food etc) of the water (the affluence), there will be tension in the social system occasioned by a systemic encroachment of the low on the high. Pressure will be brought upon the system in the contest of aspirations and goals between the haves and have-nots.

3. CONTESTING CONCEPTS

There are in the portfolio images that present the operative system of the Dust - the lowly, deprived class. But beneath this simple (rather simplistic) reflection on the organisational structure of the society is the baggage of deceptions and delusions that have kept the class (lower) perpetually chained to impoverishment: the empty promises contained in political manifestoes; the lies of the holy books and 'fishers of men'; and the grand deception enunciated in the so-called globalised culture of the internet and multimedia. The internet for instance, entrenches false values in human psyche, and in spite of its communicative merits, could instigate breeding of displaced humans (even if mentally); and economic refugees — the underlining factor behind immigration and exoduses form the Third or Fourth World to the so called First World.

4. ENVIRONMENT

Comfort & Discomfort

Images of environmental despoliation bred by faulty ambitions and goals and human misunderstanding of post-modernistic facilities of existence; or misplacement of priorities and bad planning.

Reflections on occupations that are essential to proper functioning of the social system but which are condemned eternally to the fringe of economic advantage. Those who belong to these occupations can hardly break even in a society where unproductive central business districts represent the pulse of the national wealth, even if the economy thrives trivially on influence-pushing and pen-peddling.

• At the session with Osifuye in Lagos

The Gods In Gwangju

(Abstract of discourse at the Grand Discussion at the Gwangju Biennale September 2004)

By Jahman Oladejo Anikulapo

'Is the artist God?'... The query was issued so calmly, almost weightlessly. But it sent the entire group into a deep silence; a sober reflective posture. It was a weighty question; and its impact was not lost on the gathering that afternoon.

It was the afternoon session of the Group 3 of the Viewer-Participants (V-P) that met in January, 2004 in Gwangju as part of the preparation towards the 5th Gwangju Biennale.

The discussion had been heated a while ago, when a member suggested that as a V-P, he would like to be able to tell the artist "what I want to see in a good piece of artwork".

Someone had retorted: "but you don't tell the artist what he should do, especially when he is in the creative process".

The debate trafficked to and fro; with the group of about 12 almost evenly divided... The words centered on the role expected of this strange invention of the Gwangju Biennale called the 'Viewer-Participant'.

In spite of repeated admonition, in the course of the two days of discussions -- by the Biennale's artistic director, Yongwoo Lee and his assistant curators -- that the V-Ps were not designed to usurp neither the work of the curators nor that of the creators of the art works, the artists, some of the invited V-Ps still felt that they were more important to the creative process than being mere privileged interventionists in the liason between the artist and the curator on the one hand; and on the other, between the artists and the larger public that would consume the work that would feature at the Biennale.

It was at the peak of the argument that an apparently exasperated VP declared... rather proclaimed... "Is the Artist God".

For me as a V-P, this question set rolling a thousand other questions:

Is the artist really God?

Is the curator God?

Is the so-called V-P God?

Is the audience, the art viewer (or consumer as would be appropriate in this context), God?

Is there any God indeed in the creative process?

Is there...?

Is there....?

Yet, these thousand of ponders became my guided angels in my work design as a V-P destined to collaborate with the photo artist from Nigeria, Muyiwa Osifuye.

'I had to be careful not to offend this God'... I recall warning myself, even as I was comforted by the thought that fortunately, Osifuye's ouvre as an artist, is not strange to me.

I had been a keen observer of his career ever since he emerged as an African representative (really?) in the Documenta 11, the mega-artshow in Kasel, Germany in 2003.

For a start, I was ever so reluctant to kickstart our contact. I found all manner of excuse to avoid sitting with him to discuss what he wanted to show at the Gwangju Biennale.

But deep in my head, I knew that I was only buying time; that sooner or later, we had to meet.

Gradually I eased into him through endless telephone chats and exchange of emails.

Then came the inevitable! We had to meet!!

First time was in his first floor office in Yaba Lagos. Second time at the same venue. The third time was in my own office at The Guardian, where I had worked for 16 years as an art and culture journalist, in the course of which I had been chanced to report on Osifuye's series of photo exhibitions...

I should say that it was at the third meeting... in my office... that I found my confidence to take on Osifuye and his Gwangju Biennale project.

At the end of the third session, I discovered that: The Artist is no God;

The V-P is no God.

The curator is no God.

There is no God (as applied in this context) in the creative process...

Well, perhaps the Muse...

Perhaps...

OSIFUYE's REFLECTION On HIS PRESENTATIONS AT THE GWANJU

Nurturing Global Disequilibrium

This brings to our consciousness, issues concerning the ever rising level of inequality prevalent in our times with its attendant fallout and imbalance within our global system.

This has had its roots within the basic units of human co-existence experienced at our different localities and as such has naturally extended beyond, to a multi-level of inter-relationships across national boundaries. We have the two sides of the border with a far yawning gap or better still, should we call it the two sides of the socio-economic divide: which balance is daily nurtured towards the deprivation experienced amongst a group of people within a state and across poor countries of the world-the African continent being prominent in this instance.

The struggle for supremacy in all spheres has become so heated up in recent times. While one may acknowledge that this is as an innate attribute of Man to ensure self survival, are recent actions in this pursuit of self preservation not going beyond the balance?

The less inspirational ones are daily being stampeded to the dust and ultimate death by the more privileged in the race for a nebulous ‘reward’ dreamt up by the ‘conqueror’.

The fallout is the self-inflicted tension which yet persists. Even the delicate eco-balance is not spared either.

In simple words, the reality today is the nurturing of a system which is lopsided towards a situation of grinding poverty and disrespect for human dignity.

Therefore, it may be inferred that it is possible that the human race has not actually maximized the benefits of the essence of its existence on this planet.

•Osifuye

•OsifuyeTherefore, the natural flow of thought is to question the role of our decision makers to stem the tide of this imbalance.

Across all levels of decision making one may ask: what has engaged the minds of our policy makers where issues such as the equitable share of the common good (wealth), rule of law coupled with unbiased dispensation of justice and respect for the dignity of Man are concerned? These and many questions demand our attention.

What is Man’s mission?

What is the mission of the privileged?

What is the reaction of the oppressed?

How did these attitudes originate?

Has it been as a result of retaliation or provocation? etc

However, despite these multifarious conflicting tendencies, a symbiotic relationship of sorts still prevails. Or do we call it a forced relationship- predatory in nature?

For something in return, the have-nots still serve the privileged ones within and across the socio-economic divide. A similar experience is also noted across nations where raw materials and cheaper labour force are exchanged for finished goods and services.

Yet a state of mutual suspicion, fear and tension still exist. Why? And can we do better than this?

Today, to advocate for a utopia is neither practicable nor humanly possible but our lopsided socio-economic equilibrium (being the two sides of the same coin of the human entity) ought to be steered towards a harmonious status as much as we can and not a departure from it as it were.

The oppressed nations, the weak in the slums, in the favelas, in the ghettos we know are”the dust of the earth” but let the powerful reflect on the phenomenon of our common creation and extinction to deliberately do more by allowing some spill of the needed ‘little drops of water”(at the least) touch the quaking and dried lips of these less-inspired ones.. This is what they simply ask for! To ensure a recovery, sustenance of life and restore human dignity to our other self and not mere existence as it were.

In all, life goes on albeit the uncertainties and the mutual suspicion at both ends of the fulcrum of our interactions and existence. Let us see what happens..

Muyiwa Osifuye is an African (Nigeria) based photographer. This article accompanied my photographic work at the 5th Gwangju Arts Biennale in South Korea summer 2004. A few of my works can be seen at http://www.pictures-of-nigeria.com

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/?expert=Muyiwa_Osifuye

DIALOGUE ON GWANGJU 2004

A conversation between Muyiwa Osifuye and Jahman Anikulapo on the 5th Gwangju Biennale in Gwangju, South Korea; recorded May 28, 2004, at The Guardian premises, Rutam House, Isolo, Lagos.

JAHMAN ANIKULAPO (J.A) : How do you relate to the theme of the Gwangju Biennale - I mean the contest between 'A Grain of Dust' and 'A Little Drop of Water' - in terms of the concept as described by the Artistic Director of the Biennale?

Muyiwa Osifuye (M.O): First and foremost, it's just a very simple statement but at the same time, I feel that it's a very powerful statement such that you can extend it and apply it to many spheres of life — existence, day to day activities as humans on this planet; and therefore, it's a very powerful concept. Talking about the fundamentals of life; the rudimentary; the microcosms so to speak; which can be extrapolated to macro situations. It can be applied to many things. So it is a very powerful statement and that was where I started from.

J.A: When I encountered the theme, I was enchanted by the juxtaposition of the 'Grain of Dust' and the 'Little Drop of Water'; and a lot of things was going on in my mind that: if you are a visual artist, how do you re-create such a theme that looks so abstract? You know, it could be abstract in terms of idea… I mean, it's not like saying re-create a real scene... here, you have to start from an unreal, very abstract fundaments... did you feel same way?

M.O: I think I've been fortunate in taking part in two exhibitions, which more or less had to do with looking at the context; and trying to create a kind of visual imaging to it. Documenta, which I did in Germany and the Venice Biennale. These two entailed me studying some of these things; the issues involved and at the same time, having to come up with pictorial image to, I mean, answer the questions raised by the theme

So, conceptually, I more or less saw that the 'Grain of Dust' and 'Drop of Water' as two sides of a coin which more or like tells me, first and foremost, that I would have to be involved in a kind of juxtaposition of images; not like a word and opposite as you have in the English language but of more or less showing an aspect of life from the positive perspective; and another aspect of life which is of negative perspective.

That's the way I simplified it. Of course, we have the in-between, the grey areas kind of, which more or less, I as an artist can capture an imagery; just to stimulate the kind of deep thought whereby certain photographs, you cannot really placed what am I going to say. In a way, I should say the theme is highly challenging for a photographer. If you are a painter probably, you can marry the two together; and as much as possible, the kind of photographs that I feel I can come up with are not photographs that could be twisted, or be adjusted or be modified either digitally in terms of super impositions so to speak; so more or less, each photograph cannot stand on its own, so one has to make a montage or a group of photographs which come together to give that impression or to convey that message. That was my own challenge in selecting some of these images.

J.A: At our first dialogue in your office, when you were talking about the process you went through in collecting some of the images that are now slated for this exhibition. I was wondering if the limitations of photography as an art form, was what created this problem of one picture not being able to stand on its own. This combination of images to make a complete sense of a subject; and you were even talking about getting captions; probably some kind of descriptive captions that will make the message of the picture very clear without spoon-feeding the viewer. Remember the environment in which you are recording is outside of the immediate reach of the audience. Majority of the audience that would see the works in Gwangju may just be experiencing Africa for the first time through the pictures, so one has to be very careful in not encoding the messages. Was it the limitations of photography or the nature of the theme that influenced your resolving on combination of images to make a whole statement?

M.O: I think it is partly the limitation of photography and partly the theme. The theme is very, very difficult for photography. The third factor is the people that will look at the body of work and ask themselves: 'is this man talking about each photograph singly or each photograph belongs to other groups of photographs. So, that was the issue where I came up with a caption and a small description to link up these images if they are in situ installed.

Some people might say it's not really limitation of photography in the sense that in the modern times now, you can use digital tools to come up with a photo realistic kind of image; like some painters probably would want to do. But I'm the sort of person who's more or less like a purist when it comes to this kind of modern technology. Not that I don't fancy digital intervention... or the new way of doing things. But I could put some of these images together, overlap them and try and create something. But I wanted these images to stand on their own; because each image actually sends a message. Yes! But at the same time it's like putting things together and they have a kind of synergy, and on their own too, they send a message. And as they come together collectively, they serve as a synergy.

Of course, photography has its own limitation if you really want to go the analogue; it has its own limitation. So, it behoves on the artiste to be able to do serious editing and a deep thought; both for himself and for the viewers who are going to see these works.

For me and for some elitist art connoisseurs; they might understand what you're saying if they stand and ruminate it in their mind and try to decipher 'what's this man trying to say here'...

So, in a way, the photographs may not necessarily be able to stand on their own without some little words of caption. Even though, we say photographs speak with a thousand words.

J.A: When you talked about limitations of photography; for many people, photograph for instance, means you are just recording an image. But some of the things I've seen about your work particularly, part of the portfolio that you took to Venice, what was the reception of the people in Venice to your portfolio. I mean the work was presented to a strange environment... It is not like painting, for instance... I know that painting communicates - if it's a landscape, you know it's a landscape either impressionistic or expressionistic; but photography... people may not necessarily be aware of what you are trying to say because they are not used to the image that you have presented; they don't live the experience of that kind of environment...

M.O: You are right about the photography and the limitation of the message it can transmit. When I'm shooting, I'm actually shooting based on the topic; predominantly, I'm thinking about the topic; what I'm supposed to convey. It is left for the viewers wherever, anywhere in the world to actually find out what I'm trying to say; because it would be very erroneous for me to shoot for a particular audience; if I did that, I've not done anything and I've not said anything. (I have) a particular photograph, what came to my mind was more or less ... I wanted to show a kind of a presence. There is a tailor in his shop and of course, they don't have light and I saw the window ... really, it's not a silhouette, it’s more or less like a subdued illumination there and I did not want to use flash, I had to show a reality of the situation these people find themselves and the efforts they make to survive. So, I was waiting for something to happen inside that window and of course, you won't believe that two shots were taken before the final one.

J.A: That means you caught the child in motion?

M.O: I saw him coming across the bridge over the water-way that divides all those stilt houses and I had that moment to make the photographs to have impact and again to comment that child that the future of that child might most likely be what this adult is doing here...

J.A: And that the tailor is some kind of hero to the child?

M.O: Yes! A kind of hero certainly

J.A: But he himself belongs in the reject of the society!

M.O: Yes, in a larger society.

• Conversation with Osifuye in Lagos

J.A: And that is the ambition of the child?

M.O: Oh yes, and that is despite the fact that he (the adult) made a lot of complaints about the situations; that the situation could be better than this - not necessarily talking about having all the money of this world - but getting some rudimentary equipment to use in his trade. According to him, there's a market for him, there's business for him but maybe he could not be able to raise some little money to buy some machines for his vocation.

J.A: Yeah, that is the kind of thing I said was crossing my mind; that if I don't belong to this kind of environment, for instance, how does the photography bring the message to me. The way you have explained it to me now, I don't think somebody would look at it and just quickly draw the kind of conclusion that you have just done... I was just wondering; can photography actually cut across in terms of human understanding?

M.O: Certainly, it can. I think photography is such a powerful medium of expression of documenting things; of showing the situation of things. I'm not trying to run down other areas of arts; a painter might conjure up what he feels about a situation by painting with the strokes and what have you; he can actually paint from experience and reality. But photography is so real... I'm not talking about the influence of digital manipulation, no. You capture as it is.

The moment you want to record as an artiste or a photographer could change a particular story. I could have decided to take the shots without that boy within that frame; and that's a different story. So, photography too can be a little bit rascally as a tool. So, I could decide to do anything. But, it's a reality what I have for the moment. It's something that happens and could happen. So, I could send a lot of messages by just waiting for certain moment and capture to convey this particular message about humanity; our existence and life. Existence, life, nature, name it. Because a photographer cannot take a photograph of what is not existing. Something has to be in existence before you can capture it. So, photography has to do with existence.

J.A: At the Documenta, you were present with your work at Venice, you were not there but your work was there. In Documenta, you did this massive work on Lagos, for instance, and you focused more on the environment and the inter-connection between the people and the environment; how they react to the environment in terms of actions, gestures, mood. Did you see the message that you intended, registered; or you saw people taking their different impressions of the subject, say Lagos is a chaos, an anarchy etc. Or did you see them really empathising with the kind of projections that you have since you were at Documenta, for instance.

M.O: The work I took to Documenta in Germany in 2002 that is, depicting Lagos as it were, was not an absolute form of documentary of Lagos. I am indeed, planning to do some work on that. I'm going over an extensive work which might lead up to a book on Lagos as a point of interest. Some people saw some of the works- the photographs, and someone, said that these photographs here depict poverty! Unfortunately, he was an American; and, he said the works depicted poverty. I said 'what do you mean by that?' And he said, well, I don't see anything to celebrate here'.

Now, he'll be surprised to hear that some other parts of the world in Europe, the visitors there were just seeing the efforts that people make to survive despite the lonely surroundings; the dignity; the pride, the relentlessness of people, trying to survive. Not saying that they are not aware that things could be better in terms of their environment; but they just won't give up. So, it depends on where you are coming and that determines how you are going to interpret what I show in any exhibition.

J.A: What I understand from what you said now is that every world, let's say First World, Second World to Tenth world, every world react to the images they see according to the world's individual cognitive structure; what they have internalized....

M.O: I think the word 'internalize' is better; not 'cognitive' because what you internalize most times have to do with the information you have over a period of time, the information that gets to you in your own environment. What I'm trying to say in essence is that, if you come from a particular place, a particular country, if you do not know much about what happens outside your country, then you'll be able to judge several things outside your country based on your own parameter in your own country. You need to be fully educated or aspire to get seriously educated to be able to know what are the rules in other places. It's just like a Yoruba proverb that says: "A child that says his father's farm is the largest, needs to move beyond his locality to see how big other people's farm is'.

Just like we were saying in our first set of discussions when you told me about a group of children that came from somewhere in Europe, went to somewhere in South Africa or East Africa, they were so shocked that could they move around in this kind of environment and they were crying; that they should be returned to Europe or U.S or where they came from. But after some few days, that initial shock disappeared and they've already enjoyed themselves. So, I think that has to do with the mindset and exposure.

J.A: But, where is the place of culture, for instance... I mean the cultural fundaments of a society can affect the way a human being, a person sees life. Even within Nigeria, when you talk about religion divide, ethnic divide; if you are a Christian and practise sculpture in the north, it could offend the sensibility of the community which believes in another faith.

Even in my own case, here in this office where we are having this chat, used to be my office as the Arts Editor of The Guardian, I had some art works that I put up, but the moment I stepped out of here, my successor, the man who took over from me is a Muslim, and I think sculptures are not allowed in his faith; maybe his religion does not accept putting the sculpture, I have always found the sculptures on the floor. I understand where he is coming from; the sculptures are very traditional, they look fetish according to Pentecostal definitions; so he always put the works down. That to me illustrates the fact that sometimes, religion and ethnic and cultural backgrounds or the philosophical fundaments of a person can determine the way he perceives a picture. It goes beyond the information that you have internalized.

M.O: You are right; and that's the reason why I think when such works are being put in display for the public, there should be an interaction for the public to ask the artist questions. For example, you are asking me questions right now, and I think that is what Gwangju Biennale is trying to do; to get the public through the Viewer-Participants to be involved.

There was an exhibition I had at the German Cultural Centre in February-March in Lagos this year... there were some items which I had to put together in terms of still life photography; and you had these traditional carvings which were used as toys for children. And those particular carvings, within the Yoruba culture, could be used for fetish or voodooism; and the same carvings could be used for children as toys. What I did for that exhibition was to have a kind of binary presentation; for example, a table fan and a traditional fan together; a modern toy, a western toy with a traditional toy. But on the traditional toy, somebody said the carving could be seen as a voodoo object. And I said 'you are right'. But that's not exactly what I had at the back of my mind when I was conceiving it.

J.A: During the discussion at the Gwangju meet last November, it was argued that an exhibition of this nature is something for international consumption; that it had not much for he local audience. But then, the Artistic Director said 'though we are talking about international audience, we are not going to shut out the local audience. They are the first critic of this exhibition. The whole world is coming to their backyard and they are the one hosting it and so they had a stake.

As a test of the reception of the show by the local audience, the artistic director brought some two students - I think between the age 10 and 14. They were asking them what does contemporary modern art - what you might call installation and post modernism - does it communicate with them. I remember the girl was saying that the first time she went to the Gwangju Biennale, she sat somewhere at the venue and she was doing home-work because she could not understand much of the work. This for me is a actually a microscopic review of what the general contention is about contemporary modern art. That does it really communicate? It doesn't really look like painting, sculptures and such very familiar forms. If the Gwangju Biannale is thinking very much about local audience, would you think that an environment like t he Gwangju and South Korea, that is so electronically conscious, do you think the local people can relate to the images you have here; many of them are so African in content and context. Do you think a 14-year old Gwangju girl can relate to this picture, for instance where you have clothes hanging on a pig's pen?

M.O: I think the answer is very simple, for me., Talking photography, I think it will more or less be a new revelation for such individuals; children; even for adults. You won't believe it, one of those photographs there was taken in a slum. You could imagine that there's a television screen there. When I took this photograph, the video film that was being shown for an afternoon matinee was a video production from the Far East, I think in China or Japan. And these are Nigerians who had never gone near the airport nor the seaport; who are supposed to be regarded as the down-trodden of the society. Yet, they're actually aware of what goes on in the Far East by virtue of the television video production which was made in the multi-media format. If at the initial stage they do not understand what was going on, by the time they have repeated scenes from that films from that part of the world being showed to them by share coincidence, they will start getting to know about such cultures. So, there's increase need for communication.

The images might look like a shock to some people at the initial stage but I believe it would stimulate interest; and people should be guided towards what is happening in other parts of the world. That's exactly what I feel.

It's like in Africa or in Nigeria when you're talking about the gay lifestyle or whatever, people can't just comprehend it. You can imagine a man and a man holding each other. But, somehow, we seem to be relaxing a little bit; even though it's not part of our culture. But imagine about 10 years ago, it may be unthinkable.

I think, knowledge is a dynamic thing, it has to keep on moving on. This is one of the essence of having education; to create a place for dialogue, for discovery.

J.A: Let me share an experience. When I went to the Viewers-participant meeting in Auchi, we were being driven from the airport towards Gwangju town. I kept on having this feeling that I was in a familiar environment! And I said 'I've never been to this place before but it looks so familiar. I was telling the driver and the chaperon, that I have never been here, but I seem to have been here in the past. Then, an image came to me. I just saw the stadium where they had the Seoul Olympics and the Korea- JapanWorld cup and everything fell into place. I now saw that everything I had been seeing through pictures during the games and that I had internalised them and now they have formed part of my imagfes of South Korea.

Even the 14 year old that I was talking about, I'm making an hypothesis, now who have seen these pictures of kwarshiokor African children, slums and all those things, it's just coming to me now that probably, already, they have got some degree of information about what goes on in these the images and that the pictures may not be too distant from them.

M.O: That is part of the influence of the media; influence of technology, internet and what have you. That is why education has to be stepped up especially in the Third World countries for better information because some people up to this moment, still feel that Africa is a place of negativity;, nothing positive can com out of Africa; which is very very erroneous.

J.A: When you go into environments to record, one has the impression that the people could be hostile to people coming to record them; already, there's a kind of distinction between you and them. How did you try to navigate that kind of problem where you carry camera and they see you're trying to record them in their poverty, in their squalor, in their needs, in their wants... were they co-operating?

M.O: First and foremost, you need access... these are the professional requirements for a photographer anywhere in the world. Access, because, you are not just going there to grab a shot and move away; you are going there to sink your teeth deep into the matter; you are going there to be part and parcel of that environment; so that by the end of the day when you come out, after many days of shooting, you would have got the real weight of the matter. So, it's not a paparazzi kind of thing. It means you need to do a prior research; talking to those that matter, and stating your mission; and getting permission. It's after you must have gotten permission, that you can now explore the areas, so to speak. And it might take you a week or two before you get audience because of the fact that in our own environment, we are still highly suspicious of the so-called 'strangers'; even though we are part and parcel of the country.

•J.A: For you as somebody who's shooting and observing the living conditions of these people, did you notice any resignation, or submission in the resolve of the people? Did they feel some kind of resentment, saying 'well, let him take what he wants to take, we don't care'. Or do you see them still dreaming of getting out of that rejection and depression?

M.O: It depends on the method of your approach. Some people might want to go to them and empathise with them; but they don't want it.

J.A: They don't want it?

M.O: Yes, they don't trust you, they would feel that you're trying to mock them. The situation is more or less like, of what benefit is your visit going to render to them; that's exactly what they are interested in. And their suspicion again is that whether your visit is precursor to the government coming down there and demolishing all their structures or habitats.

J.A: So, there is a suspicion

M.O: There's a suspicion; because it has happened in other places. And this is the normal thinking in any part of the world, where such slums or shanties are visited upon by whoever, making documentaries and eventually, the people are exposed and the government go there to pull down the structures; to destroy the place.

So, it is such a very difficult thing for you to get permission. Even when you have good intentions - like we are talking about right now that these things have to be shown to the policy matters so that they need to know more about assistance needed in these places, what do they want; why are they there; is it by choice; and if it is by choice, what must have caused it; what are their own aspirations, and so on. These are the things I try to tell them and at the end of the day, you find out that they trust you...

In fact, all you actually have to do is to get the leaders of such community...they have structures there; there are rules and regulations. Look at these pictures, you can see expressions, you can see seriousness in their faces, the deliberations is in session. That is like their own government.

J.A: This looks like the parliament of the town?

M.O: Yeah, the ruling power in that particular community.

J.A: This is where?

M.O: This is under the bridge Oko-Baba.

J.A: That's the settlement on the water

M.O: Yeah!

J.A: From this particular picture, you said you did not notice any resignation. Did you see hope; that they were hoping to get out of that situation; or they want to remain stuck in that situation and just continue to improve on their lives. What do they want from the larger society?

PART TWO

J.A: Following from this particular picture, you said you did not notice any resignation. Did you see hope; that they were hoping to get out of that situation; or they want to remain stuck in that situation and just continue to improve on their lives. What do they want from the larger society?

M.O: In terms of resignation, I won't say it was absolute hope or self-satisfactory. Some people are not really happy being in that kind of environment. And if you discover very well, you'll discover that those are the people who recently moved in; who have been internally displaced in the city; who did not have any choice, but just have to be there for a particular period of time, which might linger on for only God knows when. Such people, from their body language and the way they respond when you talked to them, they are not really ready to co-operate. They only listen to you because they feel they don't belong to that place. And truly, but maybe circumstances, months and years after their aspirations have failed, then, they may have to resign themselves to fate. But for those who have accepted that situation there, some not because of the fact that they could not go somewhere else, some because of the commercial activities going on, they'll tell you they are okay. But they just need some fundamentals of existence -- good sewage system, good water supply, transformer for electricity, and drainage system during terrible weather ;especially during the rainy season.

J.A: I could see some kind of differences in the way people react to your intervention. This family for instance, does not look like coming from that environment. They are not, particularly not from that environment. If I find myself in this place, I don't think I'll be comfortable with you coming around with your camera and trying to record my situation. So, there's a level of anger. I'm likely to be a bag of frustration and, when you come to shoot your pictures, I could do anything as a form of ventilating my anger. How do you capture the psychology of a person forced by circumstances of displacement to live in that environment?

M.O: I may agree with you because this particular image (CR-4-3) was a kind of scenario where I was just fortunate to get a particular image that says it all about those that come into this environment newly and still refuse to accept the reality of their current situation. This particular lady you find here, actually my camera was not turned on her, I was talking to another person -- one of those who had been entrenched in that place for years -- and she just came in newly... even my dialogue with the other person, you'll see that he was interested even though I was speaking a language the two of us understood... but somewhere along the line from the corner of my eyes, I just saw that body language that she did not belong and I had to record that. I had to capture that moment and she even turned after I clicked my camera.

She was not interested in the news I brought, judging from her reaction whether or not the government was coming to put a 5-Star Condominium for them to move in. She believes that she does not belong to that place and she does not know where she's going.

For the majority of the original residents, they have resigned themselves to fate and, have resolved they want to move on. But for those who have just come in newly into the community, it's still a shock to them. They were displaced from the more comfortable part of the city, maybe because they could not pay their house rest; they had lost their job; and have just moved into this community without the essential comforts of life, just want to be there for sometime until they can pick up their lives again.

J.A: But you don't see these new comers as contamination to the psychological build up of the environment? Now, there are some people who have been living there, they've been able to adjust themselves to their situation, they live in that environment and they've found a way of running their lives in that environment. But then, you have some people, who come in from outside with a different set of values. Are they not likely to contaminate the people there and make or push them into some kind of revolution. Is it not possible that this people who come newly to that environment can cause this people to begin to rebel even against the larger society; against their situation? Would they not bring in new values that would create some new set of problems. There's a person who lives in this kind of environment, he probably is well schooled, a university graduate perhaps... but they've have adapted, they don't have electricity, they probably don't have sewage system and water but they've been able to adapt themselves to living in that environment and making their own lives. Then somebody comes who probably might have been living in the luxurious 1004 flats (CR-5-25), this magnificent standard building, she's displaced from her well furnished flat and now she has to live in a wooden contraption without toilet facilities but the open bush, without a kitchen but the open air, without potable water but the dirty lagoon! How would she ever be part of that community; how would she ever accept the dramatic change in her situation?

M.O: Let me show you a photograph to explicate this. This (CR 5-15) is more or less appropriate. This structure was initially like this and you can imagine individuals selling all these things making their income. It's a slum, no doubt about it; and not too far away, we have the skyscrapers of the central business district. So, when you're relocated from this kind of places where new structures have to be put up for better commercial reasons, what would you not do too get back on the system that changed your living condition for the worse?

J.A: Okay, you have three levels now, the skyscrapers in the far background, this quasi modern structure, and the general slum...?

M.O: Oh yes, because this one (a new structure being built in the heart of the slum) will evolve into this, the quasi modern building.

J.A: Sorry, looks like there's already a contamination. I mean, in this setting. This (upcoming building) is looking out of place the way the structure is coming on ...?

M.O: I like to call this one a kind of glorified slum because they are close to the modern building. But those one are really down in the gutter and when you have people coming from afar newly to such places-- people who belong in the minority... I think the initial shock they have possibly does not make them to make a kind of up-rising. I don't think they would probably want to see themselves as being the leader in any kind of revolution. I think their situation is so terrible that they just lose hope. But I understand what you're trying to say; the friction that could occur when somebody comes into the slum with a better idea of what living conditions should be like, he could begin to influence the perception or passion of the people there who have accepted their fate. You could also have a situation of someone who, maybe an individual who's given a job in a local council, he lives there and everyday he comes home with raw cash because of certain amount of money that has to be given to him at the local council, if anything is going to start as an uprising, he will ensure that it is nipped in the bud...

J.A: Oh yeah, because it's going to threaten his own place?

M.O: Exactly! It's a very smart thing by the politicians making sure that such things will not arise. But from what I experienced recently, I think it's still a very selfish way of looking at existence so to speak.

J.A: The other side of that postulation for instance -- probably it's hypothetical -- if you have this kind of building springing up in the middle of this slum, is it possible that this can serve as hope, or as a future target for the people in the community? Could it lift them up in such a way that, they want to aspire to a better future? I'm playing on these three levels of of buildings in the same space?

M.O: I think I agree with you in terms of the visual stimulus i.e what we see with our eyes. I have once written that a very positive looking environment will actually affect the way we react to our current situation. You can now imagine that this kind of situation is improved, all the structures are removed and they put simple nice structures. I think the people's attitude too will change. It's not very common you find petty criminals or serious criminally minded people living in posh areas... I'm not talking about sophisticated criminals. You find armed robbers probably want to hide in a God forsaken underground. Why can't they go to a five-star hotel? What I'm trying to say is that the society influences the way you behave. So, in terms of environmental factor, the way you designed a place, the lay-out, the aesthetics of the environment influence human nature and it will determine how you are going to behave, your general tendency and sub-conscious reactions.

Just like we are here in this place, if this place were to be painted black, and everything here is smelling, dirty and what have you, in a very subtle manner, it would affect the person who works in this office. He won't know it, but the dirty inconducive environment would affect him negatively. The environment matters a lot. And that is exactly what we should be looking at. Let us have an environment that will promote positive attitude from fellow human beings; not places that look as if the world has rejected the occupants.

Look at this image (R4-26) where you have pigs and men in same living space. It is a reality. The people share the little bspace with the pigs. You can not have pigs and human beings living together and you pretend not to notice, and at the end of the day we complain that we are having more crimes. But you can have a social equilibrium when we are not treating fellow human beings with dignity.

J.A: As you were talking, I was also observing your own emotions. What was it like for you going to that place and shooting?

M.O: I don't think we can get a Utopian situation where everybody lives in peace. But I feel that once you cheat your fellow human being, you yourself, you'll ever be on your guard; and that means that you've to spend your reserved energy to be on your guard; the energy you're supposed to use for your existence, living on this planet.

There are many ways of reducing some of these negative tendencies, especially in the Third World. We could indeed, reduce some of these terrible situations. I've looked around and realised that we are just paying lip service. We have not really started respecting ourselves and returning dignity back to the people. I keep on saying it that when we were born as a child, we didn't decide -- from whichever being that must have created us -- that I was going to be a Nigerian, an American, a black, a white, born into a poor home, born to an oppressor, or to the rejected in the society! We didn't choose who we were going to be.

J.A: So, every man's situation is very circumstantial.

M.O: Yeah, circumstantial. It's so important for us to accept that situations and circumstances determine the fate of men. It reminds me of the novel by Jeffrey Archer, "Cain and Abel". They didn't tell us that both were born with five heads. They were born with the same head, with one single heart inside their body. But may be by share effort by the other chap, he decided to do something about his situation; that he will not live a poor person. I think we need to look deeply into our society. Within our own microscopic environment, extending it nationally, extending it nation to nation, so that the whole world will be at peace.

J.A: Going about this pictorial expedition, were you so passionate about it or you were just documenting?

M.O: When you are on a project of this nature as a photographer, you approach that project from the mind that you have an assignment and you'll be more academic about it. But when you start shooting, most time, you get caught up in the subject. You get involved in the subject; and at the end of the day, the images you come up with, would appear unimaginable to many people.

In fact, many photographers will tell you that you probably could have a pre-conceived knowledge of what you think you would find on the ground, but, by the time you get there, you find you are just discovering.

J.A: Okay, was it like that for you?

M.O: It was like that at any point in time; you'll find some discoveries, and you just have to record these moments. As you get involved, you are not seeing yourself as shooting for anybody, you are seeing yourself as trying to empathise.

In fact, there are images you'll refuse to record because they are just too strong; and people might miss the message. That's why painters are lucky; they can just sit somewhere and think anything.

Coming back to your question -- was I consciously aware of the situation of this environment which I covered all over the country? When I drive on the bridge, I see these people ... I've been watching them for a long period of time.

I have this interesting example of on the job empathy: when the current democratic government came in 1999, they now have what we call 'Highway Managers'. Then, I realise that they were more consistent in cleaning the well-known dirty spaces. Then, I would see cars moving at very fast speed and you see these women sweeping; of course, they have the spikes barriers on the road supposedly to prevent cars running over them; with the spikes, such reckless cars' tyres might be deflated. But the fast moving vehicle could still get you knocked and killed; which to me is more serious than ordinary tyres being deflated. And you see these women taking care of these roads. So, I got disturbed and I asked myself: if these people don't work for one day, we'll see all the rubbish, all the garbage on the highway. I wanted to know more about this; that these people are so important that we don't seem to notice them even when they are there physically. So, I took it upon myself to document their daily schedule: what goes on in their mind despite the fact that they give them some very poor pay - I won't call it salary, because they only work on schedules and so they earn wages-- which cannot even take them home. I investigated that; and I was with them for a whole working day -- right from the time route were been dished out to them to different places all over Lagos down to the dumping sites where all these refuses are dumped.

Good enough that the German Cultural Centre showed this body of work at Lagos and I think that was the first time that kind of images was showed. But surprisingly, there wasn't much that was said about that particular effort on my side. I satisfied my own curiosity, conscience and you wouldn't believe it, once in a while, when I'm driving and I see them finishing a particular portion of the road because no vehicle most times could take them back to their offices, they wait for drivers at times I pick them up! I pick them because they are human beings, they are useful, they are doing something for the society. It's like you working in an organisation here, if your cleaner does not come here and sweep this place, you can't work. Everybody has a role to play. The pilots handles an aircraft, he can't come into the cabin to serve the passengers. The stewards and hostesses cannot go behind the machine and pilot the aircraft. So, everybody has a role to play. But if you find out that the captain of an aircraft or the pilot looks down upon the hostess, you're going to have pandemonium inside that aircraft. The same thing with the flight engineers and Control Tower.

We all belong to a whole system. It's an inter-network of humans. We are both sides of the same coin. So, if you are on one side of the coin, do not feel it's a permanent desk; even if it is permanent. Someone told me that some people are born and they will never be poor till they die! Yes! And there are some people too that are born poor and they will never have sufficient.

J.A: But ambitions can cross path?

M.O: Yes!

J.A: May be two ambitions?

M.O: Yes! As in the case of Cain and Abel by Jeffrey Archer, it can, but why don't we try to reduce the gap.

J.A: When you spoke about reducing the gap, the image that came to my mind was what I have on the screen currently. Now, this (R9-11) is a posh estate (or so I assume), and then this is a gate and you'll notice that in the Nigerian environment, for instance, people build mansions and when you build a mansion, the impression is that you would want people to see that you have wealth and you have displayed it; so, you open it to the public so that everybody can see. By that you can create an iconic image or figure in the consciousness of people. But here, people build mansions and then, they build another mansion of a gate to cover the mansion they have built. And you ask yourself, but what is the essence of building such a beautiful house that nobody can see unless they get into your compound. Whereas when you go to some other parts of the world, where they have modest houses or where you call the poor living environments as in Mushin, Iyana Ipaja, Ajegunle, for instance, they don't need to build gates. Now, here is a posh gate, the gate closes permanently by 12 mid-night, 6 a.m or 8 a.m. This is a kind of prison. Why should a rich or an affluent person... who is supposedly comfortable because of his wealth and his position in the society... why should he imprison himself again. Is it a kind of contest of will going on between the two classes?

M.O: I don't think it's a contest of will between the two classes. I think it's one of the paradoxes of our lack of attitude of showing love to fellow human beings; sheer greed by people who think they're smart; the power brokers and the rulers.

You are actually right. A man puts up a structure of very fine architecture -- possibly borrowed from a foreign country, from the western world and whether it fits the climate of country of Nigeria or Africa, it does not really matter you have put up such a very beautiful structure and you want to celebrate the beauty of that house; you want to show how much money you have, whether the money was genuinely gotten or not. But because of the insecurity, because of the suspicion of your fellow human beings whom you look down upon, whom you had cheated out of the common wealth -- and you're not too sure whether they are happy at the way you have spent the commonwealth which you've cornered to yourself alone, therefore, you put up a high fence. It is ridiculous, senseless. But I've seen some photographs of some areas in South Africa, in Johannesburg, similar things happen. You put up a high fence with barbed-wire, with modern electricity-controlled gadgets, to bar people from gaining entrance into such places. Then, I'll ask myself, in the first instance, why have you put up that beautiful architecture? What you are trying to say with that architecture is a wasteful expenditure at the end of the day. And in this particular image, you have such huge houses of the so-called affluent people belonging to the same social class, fortified with high metal gates; and at the beginning of the street, a gate barricade and at the end of the street, another gate barricade; so, there isn't free movement, movement have to be made within certain limited spaces. And to me, this is more like self-inflicted punishment, self-imprisonment. What is responsible for this is because, we all know that members of the larger society are not happy with us; they are deprived and so they envy our stupendous wealth.

Yet, you probably are not thinking up any solution about it. You probably feel that as long as I can protect myself with these electronic gadgets, with whatever security in place, I can continue to sustain my existence and life on this planet... But most of the time, subconsciously, such an individual is not actually relaxed. He's not gaining the best out of the environment. How many times have you seen such people taking a walk along the street just to receive fresh air? He drives in to that enclosure, he locks up like it's done in prison yards and stays in there; he cannot even have a shrub in front of his house, or a garden; and the next door neighbour comes to him for a handshake!

It's self-inflicted punishment; and what has caused it is the greed that permeates the societies in this modern time. It also includes the inter-nation politics where certain nations' sovereignty are not respected for whatever reasons. And in the 21st century we are now, these are issues that precipitate the endless conflicts around the world.

J.A: The question of distrust between the two classes, the question of imbalances, iniquities, inequality and the absence of equity between the classes, is a solid foundation for death of peace in inter-human inter-nation, inter group relationships, no doubt. But you said your main concern was reducing the gap between the classes. What's your proposals for reducing the gaps.

M.O: My proposals are very simple, I gave you a very simple analogy. I don't know whether I'm right or wrong; that in the Third World countries, you'll find out that certain things have been put in place to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor. We talk about the middle class. The system has ensured that its middle class belongs to the masses. And when you are talking about the middle class it belongs to the majority of the population. So, I'm looking at a kind of analysis i.e. 80 per cent of a particular population have the essentials of living while the minority are either very rich or the poor.

We can even talk about the issue of taxation. In places like United States and so many capitalist countries of this world, the very rich are heavily taxed, the poor are not taxed as the very rich. The very rich find it difficult running away from paying tax because there's the system which ensures that the commonwealth is beign distributed to the remainder of the population, so that there won't be so much division. If God has given you so much inspiration -- because I know that it's inspiration and imagination that would make a man find himself at a very high pedestal level in terms of reward, which may be money or many other things -- I'm not saying, if you are lazy mentally, you should be celebrated or you should be accorded what you don't deserve and those who have used their brains, who have burnt their mid-night oil to improve their social standing or economic standing should not get the benefits; what I'm trying to say is that if some people have been genetically pre-destined to be intelligent or inspired, we should take a little from them and stimulate some other people who are not just as ambitious. Probably that will wake them up and bring out the giants in them. This happened in so many western countries, which I cherish. What it means is that we are not courting a situation where we have everybody on the same serial level, it's not possible, its not natural.

And that will still come back to the issue of the two sides of the coin -- talking about the theme of this exhibition. There's no way we have the rich without having the poor. But, I think there'll be a dislocation if you have a situation in which between the two sides of the coin one is much more prominent than the other. That's what you have in a disfigured coin.

And therefore, if you have too much sand, the system will break down. The natural system will break down. What are you going to do about the ocean and the vice-versa? We should always strike towards a balance of the forces.

••J.A: So you think the 'Grain of Dust' and the 'Drop of Water' as conceived in the theme of the Gwangju Biennale, is an attempt at some balancing?

M.O: Yes! It's an attempt at some balancing; it's a process. But, we should realise that the balancing must be in all aspects of human experience; even from the microcosm stage, say within the household where you have children, one would be better than the other, but you will realise somehow that each one of them has a gift.

J.A: The bad child also has a good side

M.O: Yeah! And that was the reason why, I said every nation should be respected, whether that nation has financial supremacy or not. There must be something special about that nation and I've never seen any nation that has it all.

J.A: But are you not breaking the whole essence of globalisation when you're saying every nation has to be respected because globalisation even though it portends or pretends to encourage sharing; and postulating that by communising some of our resources, some of our intellectual wealth that you could strike some balancing. But, the picture that has come out is that even the gap between the worlds; first, second, third, developing or undeveloped world, the gaps keep widening even with globalisation growing more wings in terms of being spread around. So, when you say that every nation must be respected, that's Utopia. Is it achievable?

M.O: Utopia to me is a situation that might not be achievable. But we can strive towards perfection... I just gave you a very good example of a country like Nigeria. We see a situation where our own form of globalisation is not existent. We say there's justice, but its selective justice. And on the global scene, there's selective justice.

J.A: Are you talking about America and Iraq?

M.O: No! I'm not talking about any country per say. It's like a Yoruba proverb that says "if I'm lying to you, and even when I proclaim I'm not lying to you, one of us will know. It is not what I say, it is my intention that says it all. The bottom line is that you cannot have peace in any society where imbalance thrives. When you have everything and the other person does not have and you pretend not to know. you will soon find out that you're not at peace with yourself; you are so suspicious of the other divide. How many times have you heard any kind of religious uprising in advanced countries that are doing very well economically. It's because the divide is seriously looked at and they ensure it's not widened. So, you'll not hear that a German-American is revolting against a Japanese-American or a Jewish-America. But in Third World countries, you find different people who are neighbours fighting each other; and the reason is so simple: because of some of these policies and some of these lack of attention to human dignity.

J.A: From what you have said now, most of the tensions and conflicts and crisis, they are more of reactions to economic situations.

M.O: Well, sort of. But it's not the actual reason, it's one of the reasons -- and it could be a major reason, depending on the situation you are considering because, there are some situations, which might be from egoistic point of view i.e. you are a superior person, I'm not. And who determines what a superior is? Can you create yourself? I've never seen any human being who has claimed that 'we are of this tribe, we created ourselves?' Or to say, 'we are more intelligent therefore we need to lord it over you'.

I wouldn't want us to see it from that economic angle alone; the economic aspect is there, the issue of inter-personality, inter- individuals, inter-nations, inter-groups and so on and so forth. So there are many reasons. But I think all in all, once we respect humanity, we'll be able to bring down the tensions and realise that we can always be at peace with ourselves if we put so much emphasis on respect for the dignity of man. In the first instance, we came into this world, not by own volition. There's a superior being that brought us here whether you are white, black, blue or yellow and you don't have any choice about that.

J.A: The struggle for assertion between the classes and the stratification in the society has been a continual discourse. I want to extend the argument to what some people have said about the contest between afro-centricism and eurocentricism. There have been the argument in the past that much of the tension that you see in developing countries like Nigeria, or in disorganised countries in Africa, has to do with the fact that, when we made contacts with foreign cultures mostly from the West -- like when Christianity and Islam came from the so-called civilisation of the First World, and that was when we started losing the very essence of real inter-persons and inter-groups relationship in the society. For instance, in the normal African community, the classes are there but the differences are not so pronounced. But in the modern African society, the classes are distinctively pursuing conflicting agenda; the society is so combustive in terms of its internal composition; so many values, which ensure internal cohesion and organism are lost. Is there any role for culture? Gwangju for instance, I look at the cause of the May 18 revolt -- which inspired the Gwangju Biennale-- and discovered it was the reaction of the people to a certain situation that they perceived was depriving them from their own human essence and fulfilment. And this is going on everywhere. So, when people feel deprived, there's distrust, there's a gap, a gulf in their psychological commitment to the society; and the attempt for them to want to cross the line to the more comforting zone always rattle the social cohesion. Even in South Africa, we recall the schisms between the apartheid lords and the miners. There was a case of the miners in Soweto trying to cross through the canal to get to the other side of the town where the affluent whites and managers of the mine live... They wake up in the morning, they're looking across the canal -- just a little distance of about 2,000 yards -- and they were looking at affluent while they live in slum and they asked: 'how come we are here and they are there?' 'Do they have two heads, two hearts?' 'Why can't we have as much or even a fraction of what they have?' You know people will always struggle to get out of their class to the greener grass on the other side! And this naturally brings a lot of tension. But people say that in the whole African society, this huge gulf between the classes was not there; even though there could be endless contests between one community and the other in terms of power relations. Could you relate the explanation you earlier gave about globalisation and the respect for each country, to your findings during this photo expedition?

M.O: I think the issue of globalisation attempted to set certain rules on the basis of which wer ought to interact with each other, but somehow, some of us are not going by the rules. It's like a contractual agreement and you are not playing to the letter, there' going to be somehow a kind of disruption.

In Africa, I think the culture is more or less like 'be your brother's keeper' whereby a parent can go on a journey and leave his children with his or her neighbours and he or she will be damn sure that those children will be taken care of. But right now, you won't believe it, in our own contemporary time in Africa, especially in Nigeria, it's no longer the issue. The tradition is breaking down; and it's creating some tensions; new form of tensions in the survival of the society. We are fast losing all those values embedded in our culture which ensures that the system works and that the level of tensions are kept down. It is all due to incursion of foreign values. Now people when they are going into public office, they swear with the Holy Bible and the Q'uran and they still go ahead to steal public funds or tell lies. You let them swear by traditional spiritual symbols or the African gods, and see if they can cheat without courting nemesis.

J.A: You know, there's a situation in our recent political history where somebody, a minister I think, was asked to swear, by his traditional god, and he said he would not swear by that; but he could swear by the Holy Bible or Q'uran, which means he was ready to lie with the Holy Bible or the Q'uran but he was so afraid of the god of thunder or small pox, which dispense instant judgement to the iniquitous.

M.O: Oh yes, the respect or fear of the potent power for the African spiritualism, our own traditional spiritualism, has made things to work. But somehow, the imported spiritualism has given us a free way to find ourselves in this kind of situation where we have derailed system and do whatever we like without thinking of any repercussion. It's very unfortunate. If Africans are trying to behave like Europeans or westerners, it's so unfortunate.

J.A: But as long as they have to relate to the westerners, to the foreign countries, you have to just abide by common practice in the world. And that is the dilemma over globalisation; it portends inescapable compromises even at the risk of losing your original identity or essence.